Case Study: Flat Tummy (continued)

To demonstrate how an influencer can utilize the TARES test we will examine a controversial Instagram post made by Kim Kardashian West. In May of 2018, Kardashian West posted an ad for a hunger suppressant lollipop from the company Flat Tummy.

In this post, Kardashian West did include #ad. Although she was not criticized for product promotion, controversy arose over the product she endorsed. Backlash stemmed from followers accusing Kardashian West of perpetuating unhealthy dieting habits. Fellow influencer/actress Jameela Jamil responded to the post referring to Kardashian West as a “terrible and toxic influence on young girls” (Mahdawi, 2018). Kardashian West deleted the post.

This example showcases how FTC disclosure regulations are not enough to conclude whether an ad is ethical or not. It further illustrates how acting unethically can harm an influencer’s public image. To better understand the functionality of the TARES test we will walk through the process by considering the above ad. As with all ethical dilemmas, your reasoning may differ from others.

The advertisement is not truthful in its claim to provide users with a flatter tummy. A Harvard medical school professor told the Guardian that “dietary supplements sold for detox or weight loss are snake oil, plain and simple” (Wong, 2018).

Effects of Advertising (continued)

Consumers

Supporters of native advertising claim that a reasonable person should be able to identify native advertising from authentic content (Schauster, Ferrucci, & Neill, 2016). However, studies have shown that a majority of people are unable to correctly identify it even with proper disclosure. (Wojdynski & Evans, 2015, Hyman et al., 2017).

A national study of college advertising students found that one-in-four could not correctly identify “sponsored content” as advertising. This study also found “one-fifth of students misidentified legitimate news articles as advertising” (Fullerton, McKinnon, & Kendrick, 2020, pg.14). For the general population these numbers are more concerning with one study reporting 92 percent of adults studied were not able to correctly identify paid content from non-paid content (Wojdynski and Evans, 2016).

This misidentification can be particularly troubling considering a Pew Research survey found that young adults (18-29 years) rated social media as their preferred platform for news consumption compared to TV, radio, and print (Shearer, 2018). By using social media platforms as their primary news source, the younger generations may be particularly vulnerable to native advertisements (Nee, 2019).

Effects of Advertising

Company

Utilizing native advertisements is a successful and profitable investment for brands (Boland, 2016). Sharethrough (2018), a native advertising agency, published a report with Interpublic Group indicating native advertisements were looked at 25 percent more often than traditional banner ads. Also, by placing ads natively, advertisers are gaining the perceived authority of the source (Conill, 2016).

In regards to brand attitude toward the sponsor, Sweetser et al. (2016) found that awareness of the content being advertising did not negatively impact the perceived trustworthiness of the sponsor. Although this attitude is dependent on the quality of the content within the advertisement.

Medium

The biggest impact native advertising holds for the mediums presenting it is gained ad revenue. Native advertisements are predicted to take up more than 74 percent of all advertising revenue by 2021 (Boland, 2016).

However, the use of native advertising may have a negative impact on the credibility of the medium particularly a print or news source (Cameron & Ju-Pak, 2000). The Society of Professional Journalists code of ethics (2019) states journalists should act independently and “deny favored treatment to advertisers.” The code of ethics goes on to highlight the importance of “distinguishing news from advertising and shun hybrids that blur the lines between the two.” As sponsored content by definition is the blurring of the lines between editorial content and advertisements, its ethicacy may be called into question.

Schauster et al. (2016) took a qualitative look at professionals in the fields of journalism, public relations, and advertising to gauge their professional opinions on native advertising. The researchers found that while their participants believed native advertising to be a necessity in the financial sustainability of the modern news model, professionals in the field found it overall unethical.

Conill (2016) further points out that by placing ads natively, advertisers are gaining the perceived authority of the source. However, it is surmised that there is a distinct difference between source credibility and message credibility. If this distinction between message and source credibility can be made by consumers, it could aid the discussion that disclosure is sufficient in differentiating advertisements from editorial content (Appleman & Sundar, 2016).

Disclosure (continued)

One thing to note when discussing disclosure placement is the concept of banner blindness. Banner blindness occurs when a web user overlooks what they perceive to be advertisements (Hsieh, Chen, & Ma, 2012). Benway (1998) theorized that users ignore banner ads because they are associated with unimportant information or “fluff.” If banner blindness can be attributed to advertisement disclosure, it may relate to how users misidentify sponsored and editorial content.

Examples of Disclosure

Discussion (continued)

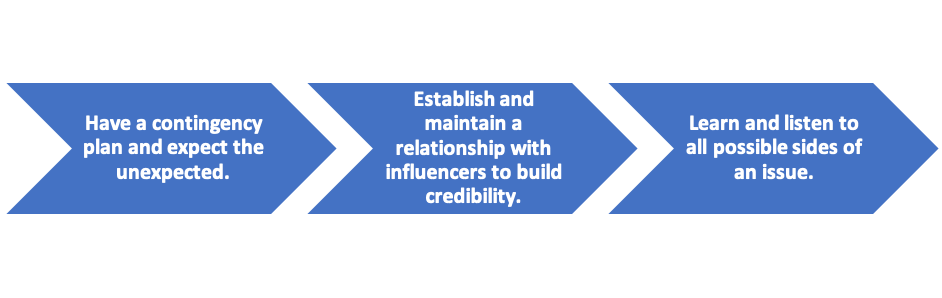

It is also important to consider recommendations from public relations professionals who have maneuvered the fake news environment. Through interviews with 21 public relations professionals in agencies and corporations, Ewing and Lambert (2019) developed strategic recommendations for combating online fake news attacks.

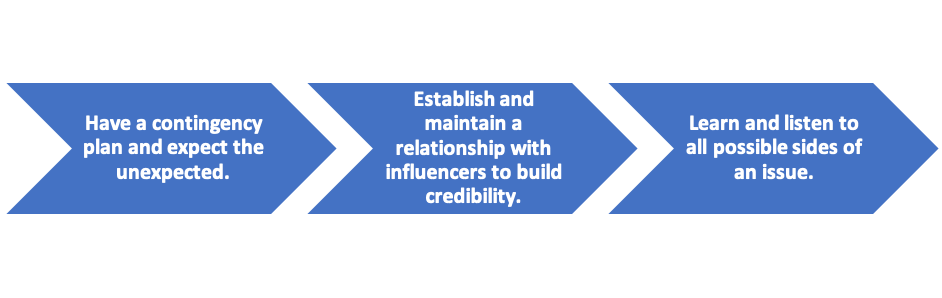

First, practitioners should have a contingency plan. If ever the subject of fake news coverage, it is better to have developed a strategic response strategy in advance. Research also revealed that during a fake news crisis, practitioners should engage with online influencers. Although this may seem counterintuitive, online influencer hold significant power. Thus, engaging influencers may aid practitioners in shaping the online conversation.

Ewing and Lambert (2019) offer the following ideas for online engagement:

- Build goodwill in advance

- Inspire advocacy

- Correct false information

- Be responsive and transparent

- Integrate media relations and social media strategies

Their findings also suggest that listening to stakeholders is a key factor in preparing for a fake news crises. Taking a proactive approach, practitioners should listen for potential issues, to identify influencers, and to include diverse perspectives.

Discussion Questions

Discussion Questions

- Compare and contrast the different types fake news.

- Reflect on your own experiences and encounters with fake news stories. Think of an instance for each level of fake news and analyze their individual public relations approach.

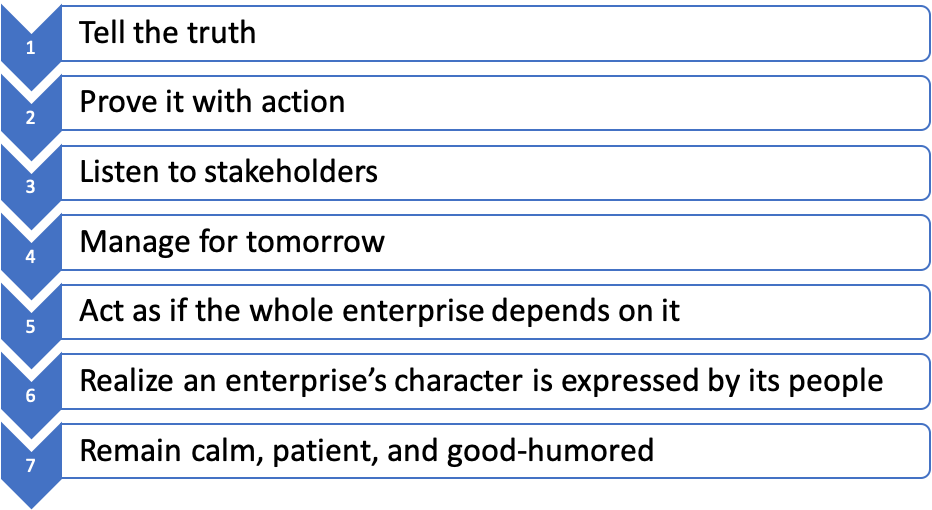

- Of all the Page Principles, which do you think is the most important ethical value for public relation professionals to uphold and why?

- With future technological developments, do you anticipate that fake news will become more or less of a problem?

- How can a client avoid being the focus of fake news?

- How can public relations professionals manage fake news crises?

Discussion

The spread of satire, parody, manipulation, fabrication, and propaganda is likely inevitable in modern society. Indeed, social media plays a large part in its imminent spread.

News is no longer simply reported by journalists or distributed by public relation professionals. The audience is also an active participant in creating and sharing news. Unfortunately, fake news stories gain power as misinformation and disinformation are spread. Practitioners need to be aware of the potential for fake news coverage and should consider ways to manage and combat fake news.

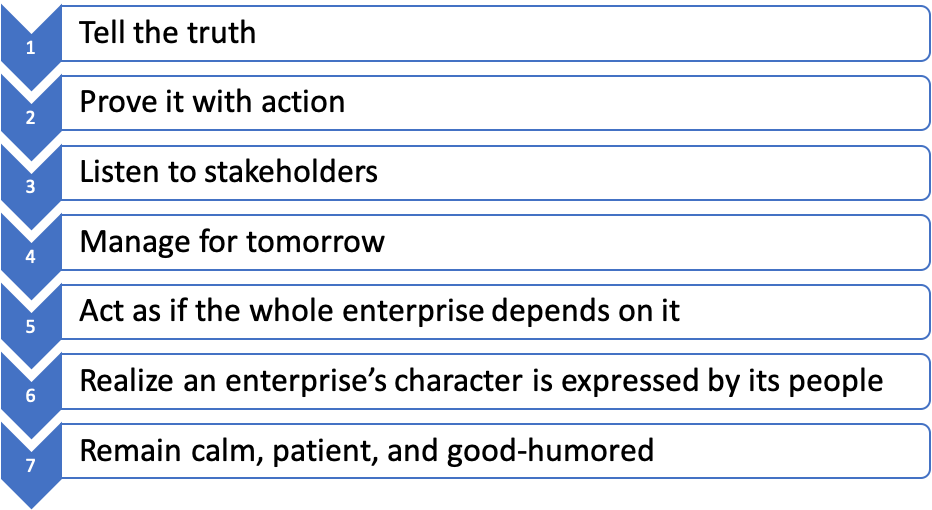

During a fake news crisis, practitioners should keep in mind the Page Principles to guide their ethical reasoning and strategic recommendations.

Case Study – Fake News Dissemination: Pizzagate (continued)

Pizzagate Case Background

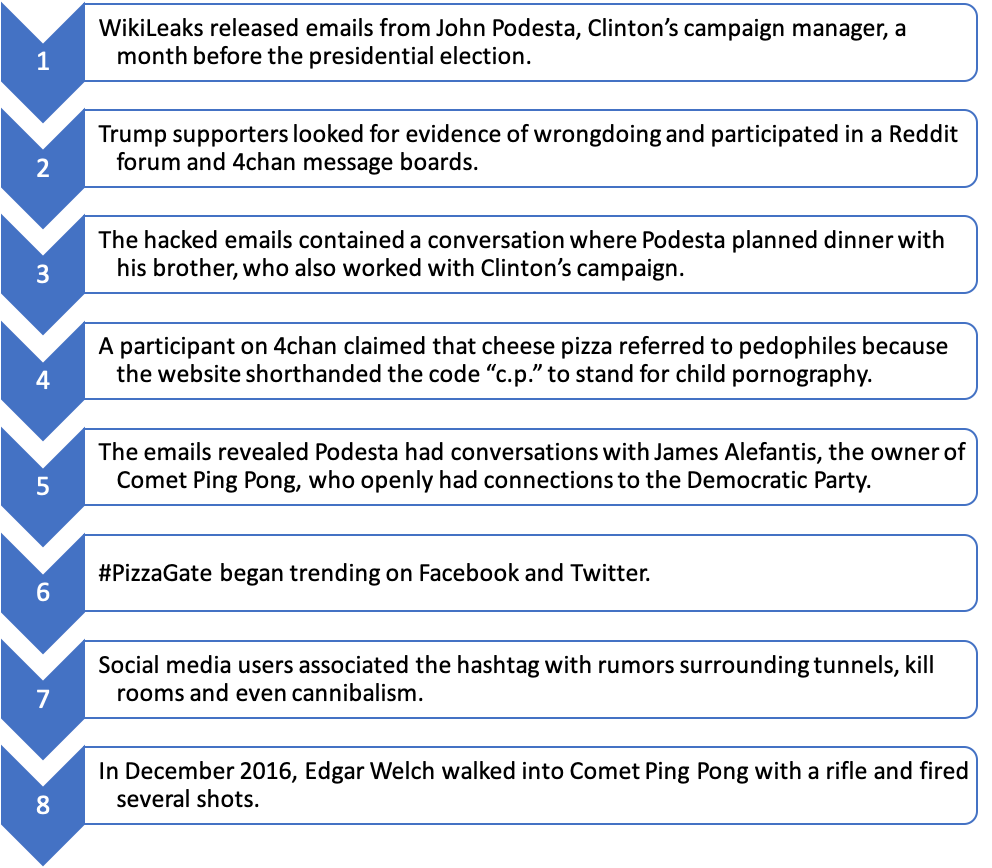

Just before the Presidential Election in 2016, a man walked into a pizza parlor and fired gunshots. While no one was injured, this incident happened because of false information being shared online.

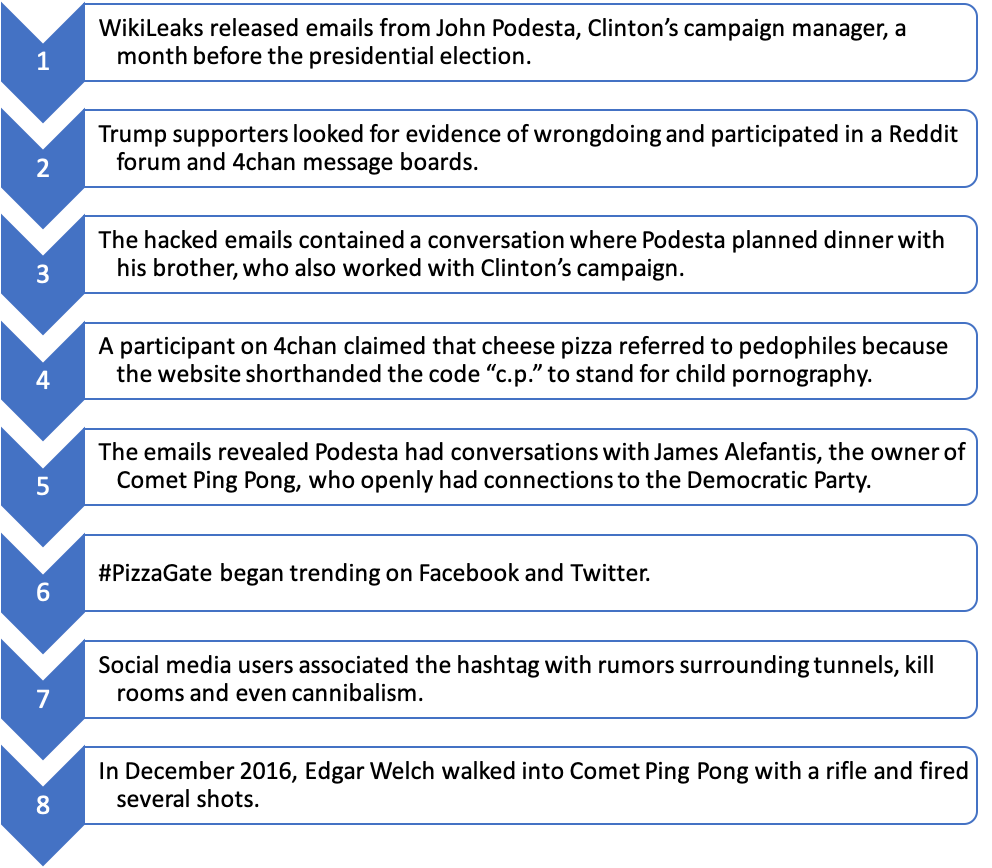

A conspiracy theory circulated on social networking sites which claimed the Comet Ping Pong restaurant, located in Washington D.C., was hiding a child prostitution ring run by Hillary Clinton and her campaign manager. This case study will examine fake news dissemination through an article published by The New York Times, written by Aisch, Huang and Kang (2016). The authors developed a step-by-step timeline briefly explaining how the fake news spreads.

Consequences

In many cases, when people ignore fake news, it spreads. However, this case study proves that fake news can still result in tangible actions. (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018). Thus, fake news can have consequences. The spread of this particular disinformation threatened much more than just a brands reputation, it put lives at risk.

James Alefantis, Comet Ping Pong’s owner, blamed the unfortunate event on the individuals who took part in spreading false information. He said in a statement to The New York Times, “I hope that those involved in fanning these flames will take a moment to contemplate what happened here today and stop promoting these falsehoods right away” (Aisch, Huang & Kang, 2016).

Discussion Questions

- Who should be blamed for the spread of fake news?

- After reflecting about the extreme consequences from the spread of fake news exhibited by the Pizzagate scandal, do you think that the accusations of disinformation went too far?

- At what point, if any, should the spread of false information be stopped?

- How would you recommend that Comet Ping Pong respond to guard their reputation?

- What should the Democratic Party have done to respond to the false allegations?

Case Study – Fake News Dissemination: Pizzagate

Dissemination

A convergence of factors in today’s digital society has resulted in a range of challenges involving the origin, dissemination, veracity and effects of many types of messaging including news, “fake” news, sponsored blog posts and native advertising, to name a few.

Contributing to these challenges are the relative ease of individual self-publishing online, the re-dissemination of messages by both individuals and organizations, the speed at which information is circulated and the blurring of age-old lines between advertising and editorial staffs – historically, “church and state” (Conill, 2016). These factors can compound the difficulty of determining the source, intent, and accuracy of much of what is consumed on the Internet and in social media.

If “fake news” is false, or only partly true, how does it spread? As simple as it sounds, sometimes people don’t realize what is real or what is fake. In fact, a Pew Research Center survey found that 23 percent of Americans say they have shared fake news whether that be knowingly or not (Mitchell, Holcomb, & Barthel, 2016).

Yet the spread of fake news stories, despite anyone’s underlying intentions, are contributing to a growing dissemination of falsehoods. Therefore, it is no wonder that 64 percent of U.S. adults blame fake news stories for confusion surrounding basic facts about politics or events in the country (Mitchell, Holcomb, & Barthel, 2016).

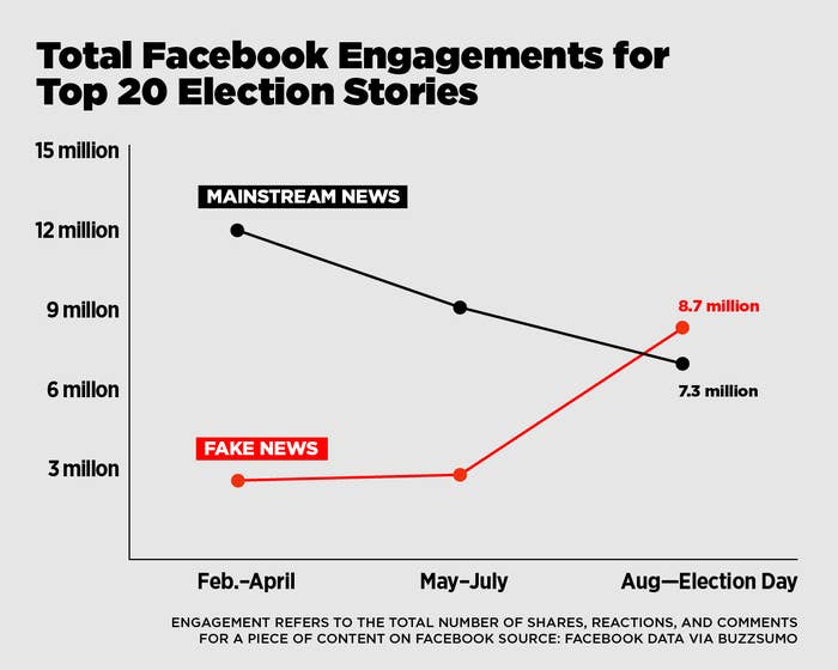

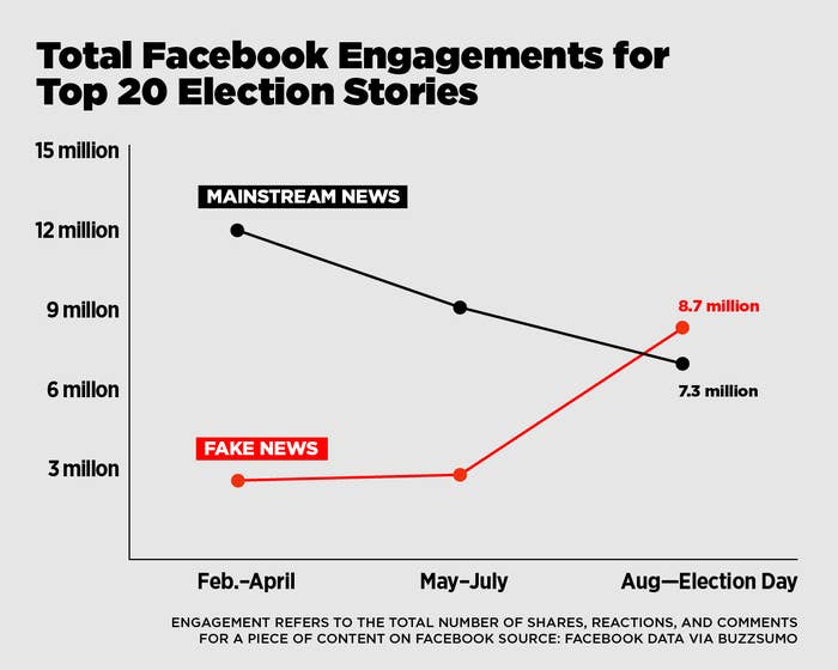

Social media networking sites have completely changed how fake news is spread. The leading networking site, Facebook, with well over 1 billion users, now is said to contribute to providing news to 44 percent of the population (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018). While the platform is enjoyed for its instantaneous connections and free flowing information, unfortunately, many users have participated in the spread of fake news stories.

In fact, a BuzzFeed News analysis found that Facebook trended more top news stories, before the 2016 presidential election, even over its major news counterparts including The New York Times, Washington Post, Huffington Post, NBC News, and others (Silverman, 2016). Unfortunately, one of those high-profile stories was Pizzagate.

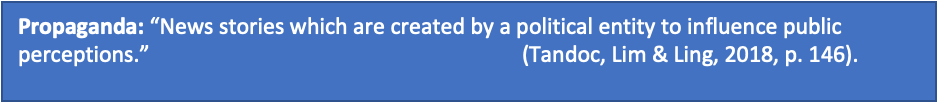

Propaganda

Finally, the last type of fake news is propaganda. Scholars define this kind of disinformation as “news stories which are created by a political entity to influence public perceptions” (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018, p. 146). It’s important to highlight the fact that propaganda often may have some plausible truth to it; however, the information is paired with strong political bias intended to persuade those who read and, or, see the presented information. (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018).

While propaganda is not commonly seen throughout the United States due to our freedoms and democratic run government, it is still a type of fake news that communicators should be able to recognize.

For example, the world has been upended by the global pandemic caused by the COVID-19 virus in 2020. Yet, the concern surrounding the virus turned from being just a medical issue to a political one.

The New York Times reported that the Chinese government had created several thousands of fake Twitter accounts in order to spread disinformation online about the coronavirus and where it initially began. Many of the social media stories claimed that the virus originated in the United States. The propaganda filled messages gained lots of traction online and resulted in a large number of retweets and likes.

In response to the widespread disinformation, Twitter took down roughly 150,000 fake accounts purposely trying to “amplify China’s leading envoys and state-run news outlets” claimed The New York Time’s article (Conger, 2020).

As time went on, government entities, news organizations, and the public became more aware of how the virus actually came to spread. As a result, the false Twitter accounts shifted their messaging in March of 2020 and began comparing the response initiatives between the United States and China. Specifically, China was referred to as the “responsible big country” in comparison to the United States who was called on to “put aside political bias,” according to The New York Times (Conger, 2020).

In response to the fake Twitter accounts, a statement was issued from the director of the International Cyber Policy Center, Fergus Hanson, who directly worked alongside the social media company to put an end to the propaganda. “Persistent, covert and deceptive influence operations like this one demonstrate the extent to which the party-state will target external threats to its political power,” Hanson said (Conger, 2020).

Manipulated Content-False Connection

While fabrication is 100 percent false, the next type of fake news actually has some truth to it. Manipulation can be described as news stories that use “real images or videos to create a false narrative” according to the scholars Tandoc, Lim & Ling (2018, p. 144). Despite there being some truth, using an adaption of imagery to sensationalize a story still misleads consumers by developing a false connection.

One example of manipulated content was an incident that widely become known as “kids in cages.” Photos taken by The Associated Press in 2014 were published with an article discussing Trump’s immigration story claiming that the administration had “lost track of nearly 1,500 immigrant children” according to the AP. The story trended on social media and grabbed the attention of many due to its particularly compelling images of kids confined behind what looks like a fence. One tweet, by Antonio Villaraigosa, the LA mayor, wrote “Speechless. This is not who we are as a nation” (Flaherty & Woodward, 2018).

The compelling photo was in fact real and Trump’s immigration policies were reported accurately; however, the photo placed next to the news story manipulated the content to indicate differently. In response to these allegations, President Donald Trump himself tweeted, “Democrats mistakenly tweet 2014 pictures from Obama’s term showing children from the border in steel cages. They thought it was recent pictures in order to make us look bad, but backfires” (Flaherty & Woodward, 2018).

While there may be some truth to manipulated content, the falsehoods overshadow otherwise important facts or information. Given that Trump popularized the term “fake news” in the wake of the presidential election, incidents that question the credibility of otherwise trusted sources continue to contribute to the lack of believability from consumers. If something is only somewhat true, then it is still fake news.

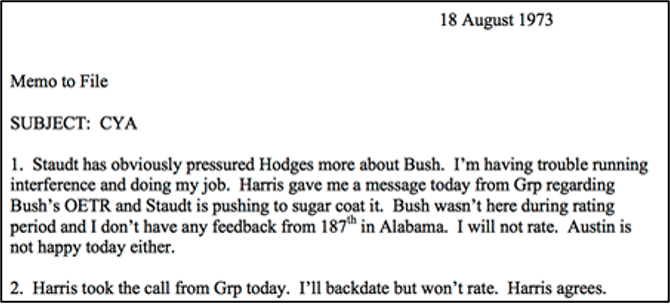

Fabricated Content/Imposter Content (continued)

It is important to realize that it is not just the public who can be misled by entirely false information. Unfortunately, sometimes credible news outlets are fooled and often they may not realize it until it is too late.

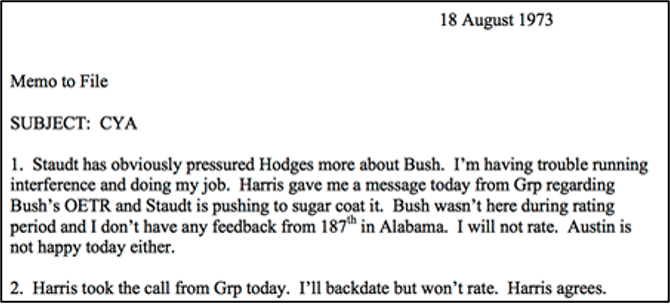

One instance, referred to as Rathergate, demonstrates just how strong fabricated messages can be. In 2004, Dan Rather, a journalist for CBS, presented six documents during an episode of the broadcast TV show, “60 Minutes.” The files being discussed, known as the Killian documents, contained information about President Bush’s service in the Texas Air National Guard (Rutenberg and Zernike, 2004). The news was believed until only two months before the presidential election happened. Breaking news reported that CBS failed to factcheck the documents before broadcasting it to the public.

It was later learned that the Killian documents were not written on a typewriter in 1973, but instead created on Microsoft Word (Rutenberg and Zernike, 2004). The experts suggest it would have been impossible to develop such a document that many years before.

In response to the allegations, Andrew Heyward, the CBS President said, “We should not have used them. That was a mistake, which we deeply regret," according to an article written by The New York Times by Rutenberg and Zernike.

Additionally, Rather, the CBS reporter, also gave a personal statement regarding the fake news story that got him fired. He writes, "I want to say personally and directly I'm sorry" (Rutenberg & Zernike, 2004). This is just an example of how powerfully persuasive messaging can be. Often, timing is a key factor to the spread of political fake news stories. One might only image how the courses of history would have changed if the files were not declared as yet another believable “fake news” story.

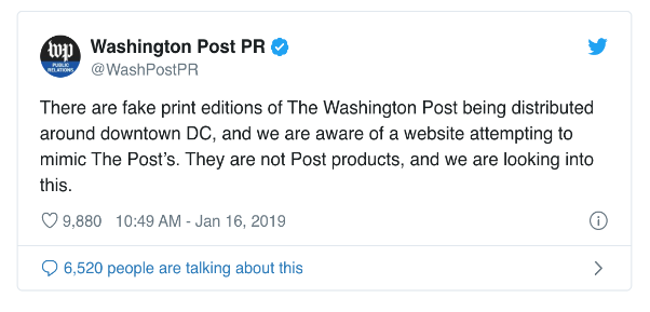

Fabricated Content/Imposter Content

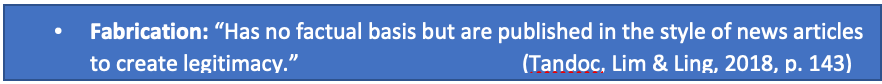

While satire and parody play on humorous attacks, this first level of “fake news” does not require immediate attention due to its widely acknowledged entertainment value. However, this next level of fake news, fabrication, requires a different response due to its lack of facticity and intent to deceive.

This type of information has no factual basis; however, the stories are presented or “published in the style of news articles to create legitimacy,” and often are believed to be a trustworthy source because partisan organizations often present information with some neutrality (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018, p. 143).

According to the scholars, Tandoc, Lim and Ling (2018) research acknowledges that this type of information is often spread for the purpose of financial gain or now, more frequently, by artificial intelligence online sources.

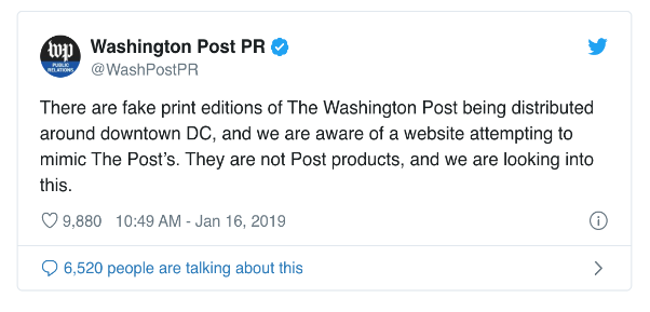

On May 1, 2019, newspapers, appearing identical to The Washington Post, were distributed on the streets in Washington D.C. The headline, “Unpresidented,” appeared in large bold letters alongside a story which claims President Trump resigned from office. According to one of The Washington Post reports, the purpose of the newspaper was to show “the future and how we got there — like a road map for activists,” said Jacques Servin, a leader of the initiative (Heil & Farhi, 2019). The article also points out that the collection of fabricated materials cost nearly $40,000 to print and distribute which signifies the level of planned intention and commitment of spreading disinformation (Heil & Farhi, 2019).

In response to the distribution of look-alike newspapers, The Washington Post took immediate action by issuing a disclaimer warning that the paper was not legitimate on their Twitter account, “Washington Post PR.”

This was an important effort by public relations professionals because they shined light on the spread of disinformation as quickly as possible before releasing an official response. Later on, a spokeswoman Kris Coratti, responded by writing, “We will not tolerate others misrepresenting themselves as The Washington Post, and we are deeply concerned about the confusion it causes among readers. We are seeking to halt further improper use of our trademarks” (Heil & Farhi, 2019). While communication professionals may not have the ability to stop fake news stories from happening, implementing an instant response, by utilizing social media, can quickly stop false information, as fast as it is being shared.

Satire and Parody (continued)

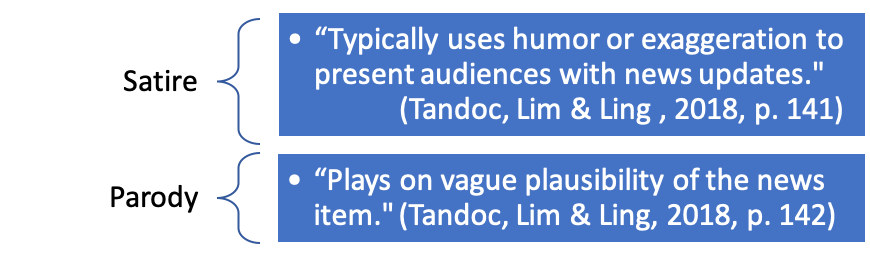

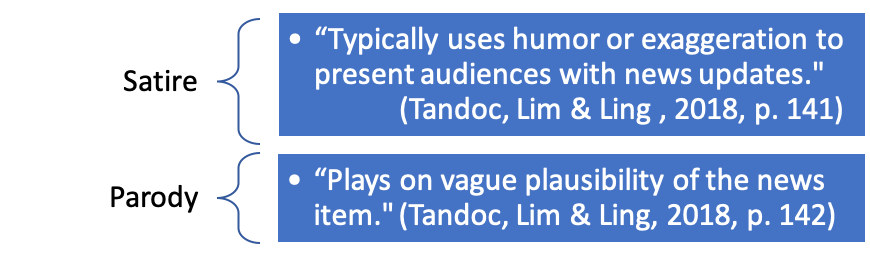

It is important to note that studies include satire and parody under the category of fake news because of their formatting. Unlike other types of misinformation, satire and parody have no intention to cause harm which significantly separates the two from other types of fake news. Because of this, there is some controversy surrounding the spread of this type of information. On one hand, scholars like Tandoc, Lim and Ling (2018) claim humorous articles and trendy social media headlines can help people become aware of cultural events.

Yet, at the same time, research also proves that satire and parody sites can have a strong influence on a person’s belief system and may be more persuasive than people might think (Tandoc, Lim and Ling, 2018). When criticized for encouraging “fake” satirical sites, like The Babylon Bee, by mainstreamed journalists, The Babylon Bee’s Editor in Chief, Kyle Mann, responds to his critics, ironically, through satire (Andros, 2020).

Satire and Parody

Content that typically makes fun of news programs and uses humor to engage with their audience members can be classified as news satire (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018). Often, the overall intent of spreading this type of information is to provide entertainment by suggesting humorous critiques of political or pop cultural events.

For example, Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” is an example of a highly appraised fictitious news program that uses satire to poke fun at current events. While still categorized as “fake news,” satirical information does not come from journalists, but rather comedians or entertainers (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018).

While similar to satire, parody is another type of fake news. The difference between the two is simply a function of how the humor is used. “Instead of providing direct commentary on current affairs through humor, parody plays on the ludicrousness of issues and highlights them by making up entirely fictitious news stories,” according to the scholars, Tandoc, Lim and Ling (2018). Specifically, political parody outlets capitalize on the “vague plausibility of the news item” (p. 142). The Babylon Bee is a leading parody site where they claim the motto, “totally inerrant in all its truth claims.”

Types of Fake News

Lesson 1 provided an in-depth look at one of the most pervasive types of fake news: native advertising. With native advertising, the persuasive message content is generated by the client. Thus, native advertising and other sponsored content allows strategic communicators the opportunity to shape the media content.

Lesson 2 focuses on the remaining types of fake news: satire, news parody, fabrication, manipulation and propaganda (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018). With these types of fake news, the organization does not create the editorial content. Instead, it is often the target of the messages created by a third-party source.

Therefore, public relations professionals must understand the types of “fake news” that could potentially threaten their clients or stakeholders.

From a public relations perspective, it is important to consider fake news types focusing on both facticity and level of deception.

By examining fake news stories, as well as strategic responses, PR professionals can understand how to successfully and ethically respond to fake news stories.

While the ultimate goal of news coverage may differ for journalists and public relational practitioners, both professions operate under the same ethical principle of telling the truth.

However, truth, itself, is now at odds with a cultural shift where people often associate news with the word “fake.” Despite the lack of an agreement upon definition and the various types of fake news, the phenomenon has critical implications for the functioning of a democratic society, press freedom, individual citizens and professional communicators.

Fake News Content

A convergence of factors in today’s digital society has resulted in a range of challenges involving the origin, dissemination, veracity, and effects of many types of messaging. Contributing to these challenges are the relative ease of self-publishing online, the re-dissemination of messages by both individuals and organizations, the speed at which information is circulated, and the blurring of lines between advertising and editorial content (Conill, 2016).

These factors often compound the difficulty of determining the source, the intent, and the accuracy of information consumed. While the ultimate goal of news coverage may differ for journalists and public relational practitioners, both professions operate under the same ethical principle of telling the truth. However, truth, itself, is now at odds with a cultural shift where people often associate news with the word “fake.”

With truth called into question, the definitions of fake news vary. Legal analysts confine the definition to “online publication of intentionally or knowingly false statements of fact” (Klein & Wueller, 2017, p. 2), while other scholars include political “spin,” propaganda, and native advertising (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018).

Fullerton, McKinnon and Kendrick (2020) conclude that “fake news” includes content that may be misleading, sensationalized or deliberately false.

Indeed, “fake news” is a very broad term. To develop a typology, Tandoc, Lim, and Ling (2018), reviewed 34 academic articles focusing on “fake news” that includes six categories: news satire, news parody, fabrication, manipulation, advertising, and propaganda.

Often the contributing factor to understanding fake news is the content’s motivation. While it may seem obvious to distinguish credible news from “fake news” stories, it is not. Results from a 2016 Buzzfeed survey found that “fake news headlines fool American adults about 75% of the time” (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018, p. 137). Fake news stories may be more obvious to the audience, such as humorous stories trending on social media.

However, fake news also may be advertising that is strategically crafted to look like editorial content while promoting a more meaningful agenda (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018). Despite the lack of agreement upon “fake news” definitions and categorization, the phenomenon has critical implications for the functioning of a democratic society, press freedom, professional communicators and individual citizens.

Lesson 2: Fake News Content

President Donald Trump popularized the term “fake news,” using it to describe negative news coverage during the campaign and after his 2016 election. After Trump’s inauguration ceremony, media disputed whether the audience size was accurately reflected in his description of the enormous crowd. Responding to the inauguration coverage, Press Secretary Kellyanne Conway coined the term “alternative facts” (Fandos, 2017).

Since Trump took office, his accusations of “fake news” coverage have increased and his description of what is “fake” has expanded. According to Keith (2018), Trump’s tweets about news that he deems “fake,” “phoney,” or “fake news” has increased both in scope and frequency. These tweets reference “fake books,” “fake dossier,” “Fake CNN,” and “fudged news reports.” An NPR Analysis of Trump’s tweets found that he included the words “fake news” in 389 posts (Keith, 2018). Not only has media content been called into question, but trusted news organizations have been labeled as “fake news” providers.

Case Study (continued): Authenticity

Authenticity refers to the persuader's use and honest belief in the product. While the Instagram ad does depict Kardashian West with the lollipop in her mouth there is no indication that it is a product she uses on a regular basis.

An anonymous staffer from Flat Tummy who helped direct influencers on their Instagram photos alluded that they did not expect influencers to actually use the product they were promoting (Wong, 2018). It can be argued that by not being a genuine user of the product, Kardashian West is not showing due respect to her followers.

Regarding equity, there was an imbalance between knowledge presented in the ad when compared with knowledge the buyer would need to make an informed decision about purchasing the product.

Social responsibility can also be questioned in this ad. Critics of the ad pointed out that the timing of the ad being posted during Mental Health Awareness Week was especially troubling (Mahdawi, 2018). An estimated 20 million women and 10 million men in America have struggled with an eating disorder according to the National Eating Disorders Association (2019). Ads such as those for Flat Tummy lollipops perpetuate an unhealthy and irresponsible view of body expectations (Wong, 2018).

In this case, it also is important to consider the difference between law and ethics. The post followed FTC disclosure guidelines and was therefore legal. Instagram does have policies in place to lessen the inclusion of ads that may show a negative self-image (specifically warns against before/after photos and zoomed body parts) in order to sell health, fitness, or weight loss products. However, the policies apply only to paid Instagram advertisements.

The policies do not apply to the Kardashian West post and to other posts from paid endorsers (Wong, 2018). Today, the Instagram “flattummyco” has 1.7 million followers. In its rise to success, it has focused the majority of its marketing efforts on social media (Wong, 2018). Although Kardashian West, suffered backlash from the initial Flat Tummy lollipop post, she and her sisters have since endorsed other Flat Tummy products, including Flat Tummy shakes and Flat Tummy tea. With the subsequent posts, online backlash also has followed (Nzengung, 2019; Zollner, 2020). It is the questioned unethical actions, not legal infringement, that has caused backlash for the Kardashians as Flat Tummy endorsements. Although the sponsored posts are legal, the application of the TARES test may indicate they are not necessarily ethical.

Discussion Questions

- If Kardashian West put her decision to post about the Flat Tummy lollipop through the TARES test, would she have realized the ethical questionability of the company?

- Would she have decided to promote the product?

- Would she have experienced the backlash and harm to her public image?

- What would you have advised Kardashian West to do in this case?

Case Study: Flat Tummy

One of most successful forms of native advertising is the use of social media influencers to promote products on social media sites. An influencer is defined as an individual with a large social media following who uses that clout to persuade people to purchase products or services (Kirwan, 2018).

Influencers are generally considered to have an expertise in a field in which their followers share an interest such as fashion or food (Hall, 2016). This perceived expertise gives the influencer a greater effect in persuading their followers.

Instagram, the photo sharing social media application created in 2010, has grown its user base to include a recorded 37 percent of Americans in 2019 with 67 percent of those users being between the ages of 18-29 years, according to a Pew Research survey (2019).

Advertisers have successfully moved into this space by utilizing influencers. Ninety-four percent of marketers found influencer ads to be successful, providing 11 times the rate of investment when compared to traditional advertisements (Ahmed, 2018). In 2016, 40 percent of Twitter users reported that they had purchased something based off an influencer’s tweet (Karp, 2016).

One aspect making influencer marketing so successful is that influencer ads are considered to be more authentic than traditionally branded ads (Talavera, 2015). Furthermore, Swant (2016) found that people rate influencer opinion equal to that of their friends.

Credibility is an important factor for influencers as it directly impacts their ability to persuade their followers (Hall, 2016). Lou and Yuan (2019) found that influencers' trustworthiness or credibility resulted in more positive thoughts toward the brands the influencers were promoting. To enhance credibility, many brands pay celebrity endorsers to advertise their product.

According to Wong (2018), the Kardashians are reported to collect six-figure payments for their sponsored Instagram posts.

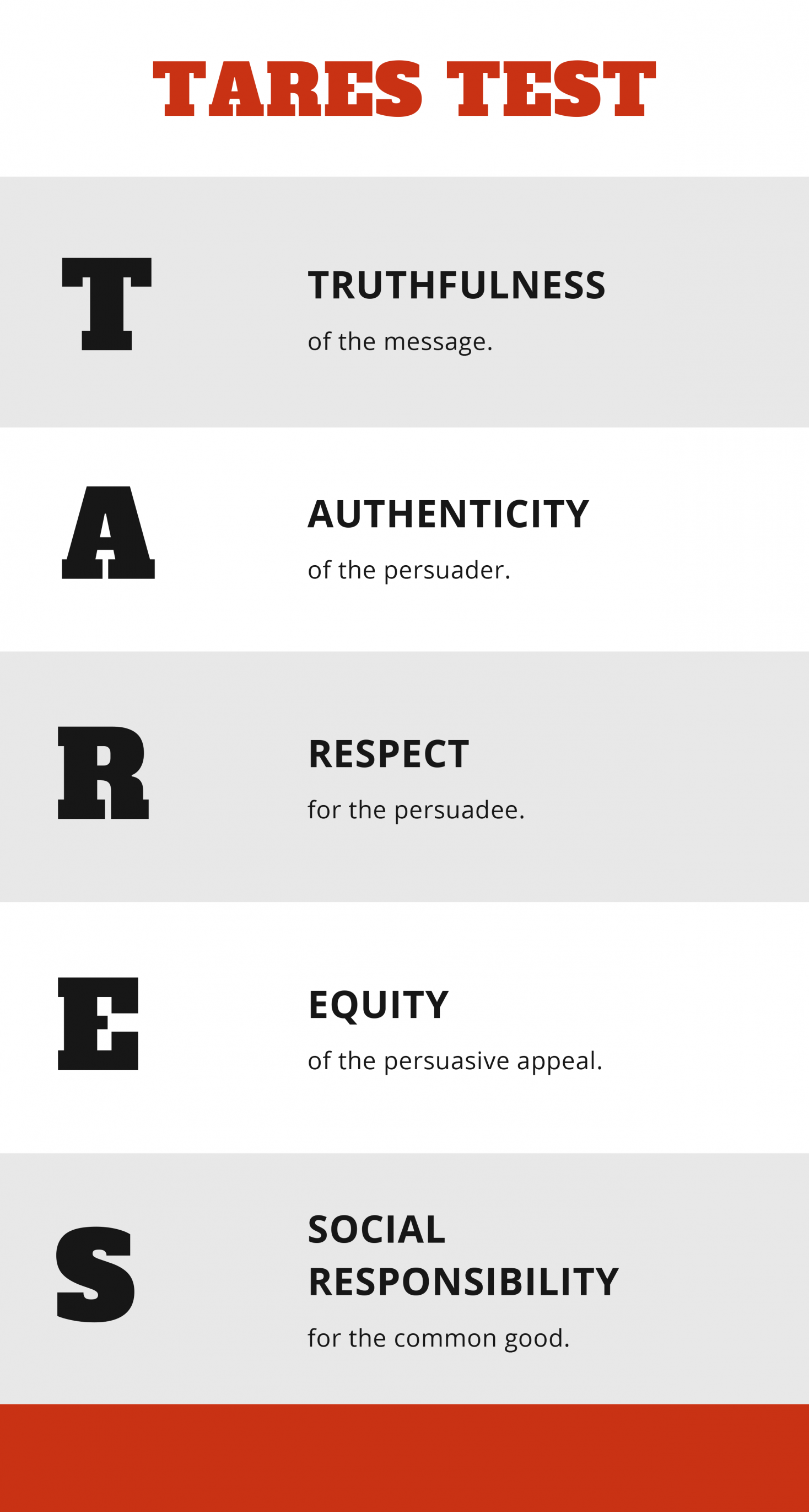

Social Responsibility and Ethical Decision Making

Baker (1999) explained that a communicator must consider their responsibility to the community over that of their raw self-interest. Self-interest in this context includes profits and career success. The common good in social responsibility signifies that, as persuaders are members of the community, the overall benefit to the community should be examined when creating persuasive messages (Baker & Martinson, 2001). Moyers (1999) argues that persuaders are a privileged voice in society and as such share a responsibility to improve and not hinder the communal well-begin. Persuaders should consider social responsibility on both the macro and micro levels. They must consider how each message will affect an individual and group and balance that information in order to create a message that positively impacts society (Baker & Martinson, 2001).

To measure the social responsibility of a message ask yourself the following questions:

| Does this message help or hinder public trust? (Bok, 1989) | Does this message allow for consideration of opposing views? (Moyers, 1999) | Does this message create the opportunity for public dialogues? (Cunningham, 2000) |

| Will having, or not having, this information lead to harm for individuals or groups? (Fitzpatrick & Gauthier, 2000) | Have the messages’ potential negative impacts been taken into account (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Does this message unfairly depict groups, individuals, ideas or behaviors? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) |

Balancing the Elements of the TARES Test

It is important to note that at times the elements within the TARES test may conflict with one another. This conflict results in an ethical dilemma. Kidder (2009) defined an ethical dilemma as a ‘right-versus-right’ decision. With any ethical decision-making situation, there is not always a clear correct answer. For instance, when being truthful can negatively impact the public, an ethical dilemma occurs, calling for the need to question the social responsibility of the piece.

In ethical decision making there is not always a clear answer. The TARES test is designed to start a conversation in order to make the messenger consider the ethical implications of the message. Each element should be compared and weighed against the overall good versus the overall evil of the message and the potential ramifications of the message.

Respect and Equity

Respect for the Persuadee

Respecting the persuadee means the persuader does not see the persuadee simply as a means to the end of selling their product or idea, but rather that the persuader considers the ramifications of any messaging on the persuadee and the public at large (Baker & Martinson, 2001). The well-being of the persuadee must be called into question and considered in any form of messaging so that the persuadee may make a well-informed, uncoerced choice. This concept goes back to the idea that the results of the action are equally important as the action itself.

Asking yourself the following questions will aid you in insuring you are treating the intended persuadees with respect as consumers and individuals:

| Does this message allow persuadee to act with free-will and consent? (Cunningham, 2000) | Does this message pander to or exploit its audience? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Have I taken the rights, and well-being of others into consideration with the creation of this message? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) |

| Will the audience benefit if they engage in the action the message portrays? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Does the information adequately inform the audience? (Cunningham, 2000) | Is the message unfair or to the detriment of the audience? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) |

Equity of the Persuasive Appeal

In the TARES test, the terms equity and fairness are used interchangeably. Equity refers to the balance of treating each persuadee with the same level of respect and concern. Persuasive appeals must not unjustly target a demographic without the ability to comprehend the message or exploit vulnerable populations. Exploitation refers both to the message itself and the motivations of the persuader. The TARES test specifically tasks communicators to examine their messaging, not only from their own perspective, but also to consider the intended audience to determine if the message is equitable (Baker & Martinson, 2001).

Asking yourself the following questions will help to determine if the message is equitable to all involved and to those targeted:

| Will the audience understand they are being persuaded not informed? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Have I unfairly targeted a specific or vulnerable population? (Patterson & Wilkins, 2014) | Would I feel this message was equitable if presented to me or someone I love? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) |

| Does this message exploit a power differential? (Gauthier, 2000) | Does the message take into account the special needs or interests of the target population? (Cooper & Kelleher, 2000) | How can I make this message more equitable? |

Truthfulness and Authenticiy

Truthfulness of the Message

Trust is essential in the field of public relations and presenting misleading information or misrepresenting information breaks that trust. In order to maintain trust, it is important that public relations professionals be truthful in their messages. Truth in this context does not mean only literal truth, but also conceptual, complete, unobstructed truth (Baker & Martinson, 2001).

To determine if a message is expressing the full complete truth, ask yourself the following questions about the message you are crafting:

| Has the message deemphasized important information? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Does the message represent the whole, complete truth? Was information left out in order to misdirect the persuadee? (Deaver, 1990) | Would I feel the message were complete if given to me in the provided context? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) |

| Does the message lead people to believe what I myself do not believe? (Bok, 1989) | Is the information withheld critical in allowing the persuadee to make an informed decision? (Fitzpatrick & Gauthier, 2000) | Does the message deceive people either explicitly or implicitly? (Bok, 1989) |

Authenticity of the Persuader

The TARES test focuses on the responsibility the communicator carries in developing messaging. As such the authenticity of the persuader must be called into question. When crafting messaging, you must evaluate your own motivations, loyalties, and attitudes regarding the message (Baker & Martinson, 2001). In order for the persuader to be authentic in their actions, they must believe in the product or idea they are communicating to the public

To explore your own authenticity on a matter ask yourself the following questions:

| Do I personally believe in this product? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Do I personally believe the persuadee will benefit? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | By putting out this message am I perpetuating corruption? (Martinson, 1999) |

| Is this cause or product something I would personally advocate for? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | In participating in this action is my integrity being called into question? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Am I happy to take responsibility for this message? (Waltz, 1999) |

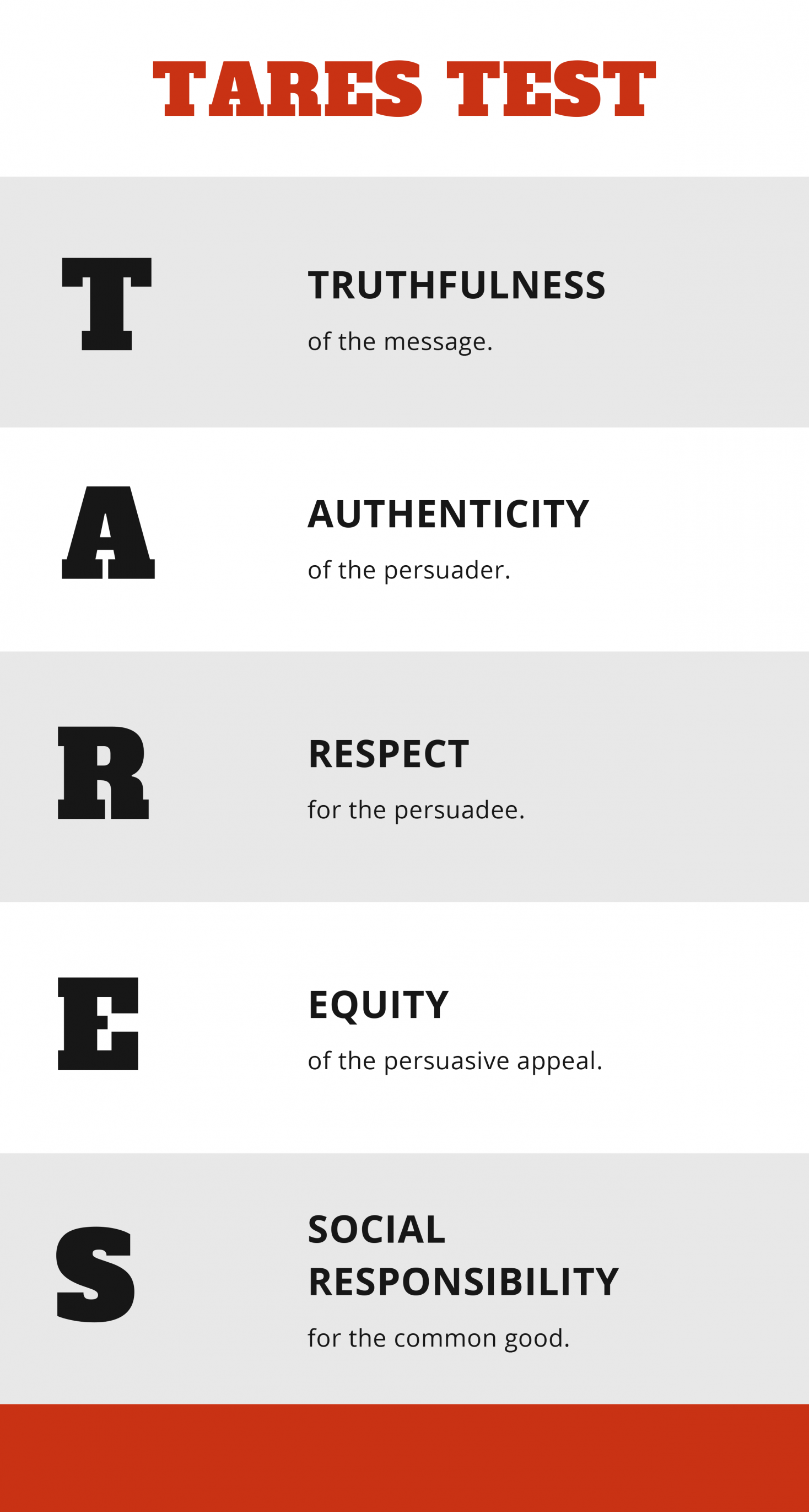

The TARES Test

An important part of ethical decision making is the ability to defend your choices. To aid in this process, we will examine the TARES test as a guide for making and defending ethical choices. The TARES test was developed by Baker and Martinson (2001) to focus on five principles for ethical persuasion. This framework functions under the theory of utilitarianism, which maintains that the results of an action are equally important to the action itself when evaluating its ethicality (Patterson, Wilkins, & Painter, 2019).

TARES is an acronym for truthfulness (of the message), authenticity (of the persuader), respect (for the persuadee), equity (of the persuasive appeal), and social responsibility (for the common good). These attributes are echoed throughout varies codes of ethics in the communication field including that of the Public Relations Society of America.

Disclosure

Wojdynski and Evans (2016) pinpoint two distinct factors that are required for successful disclosure of sponsored content. First, consumers must notice the disclosure itself. Second, consumers must comprehend what that disclosure means in reference to the content they engaged with.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) mandates every paid post be disclosed with language such as “#ad,” “sponsored content,” and “paid content.” It further demands that disclosures be:

- In clear and unambiguous language

- As close as possible to the native ads to which they relate

- In a font and color that’s easy to read

- In a shade that stands out against the background

*for more information regarding FTC native advertising disclosure go here

However, it is important to note that law and ethics are not the same. Law stresses what you must do, while ethics considers what you ought to do.

Disclosure language can impact an individual’s ability to correctly identify the content as advertising. With a variety of disclosure language utilized, consumer confusion and their inability to correctly identify native advertising may occur even when disclosure is present. Disclosure language that has been tested to have the greatest correct identification include: “paid ad,” “paid content,” “this content was paid for by,” “paid post,” and “ad” (Hyman et al., 2017). While other terms such as “brand voice” have been used by online publishers such as Forbes, they are not as readily identified as native advertising (Moore, 2014). Disclosure language, size and placement is important in signaling to the reader what they are viewing is an advertisement.

Trust

Persuasive communicators should consider ethical issues on both the macro and micro levels. Without considering the ethical impact, the overall distrust of communicators may increase. Baker and Martinson (2001) explain that the public exhibits distrust in communicators “because they fear those in the field do not respect them as individuals and are interested only in achieving immediate and narrowly defined self-interest goals or objectives” (p. 165).

To build trust with the community and to get the most out of persuasive messaging is of high importance to communicators. It is to the benefit of public relations professionals, the organizations they represent, and society as a whole to consider ethical issues when crafting native advertisements.

Lesson 1: Native Advertising

Native advertising is defined as “any paid advertising that takes the specific form and appearance of editorial content from the publisher itself,” (Wojdynski & Evens, 2016, p. 157). In essence, native advertising is the use of advertisements which are disguised as authentic content. Fullerton, McKinnon, and Kendrick (2020) define fake news as content that is intentionally misleading, sensationalized, or deliberately false.

Native advertising mimics the look and feel of authentic content and falls under the umbrella of fake news.

One of the most common forms of native advertising is that of sponsored content. Ikonen, Luoma-aho, and Bowen (2016) describe sponsored content as a hybrid between advertising and journalism. Companies pay content providers to create articles which paint their product, service or idea in a positive light and then place those sponsored articles within the context of the independently written editorial medium. “It is about creating content that is so appealing that the potential customer wants to enjoy it, unlike advertising which is generally just disliked and skipped” (Lehto & Moisala, 2018, p. 3).

For sponsored content to be successful, the articles must look real. However, because the advertisements look like real articles, the audience may be deceived into thinking it is a credible editorial, not an advertisement (Schauster, Ferrucci, & Neill, 2016).

Making the Business Case for Diversity

Some researchers point out that while improving diversity is the right thing to do from a moral or ethical perspective, it also is essential from a business perspective. Diversity in the public relations workplace can help stakeholders such as employees, shareholders, and customers.

But the bottom line is this: The more diverse a company is, the more money it is likely to earn.

A 2018 McKinsey&Company study involving over 1,000 companies in 12 countries found the following regarding profitability and economic profit margins:

- Companies ranking in the top quarter for gender diversity at the executive level were 21 percent more likely to outperform their peers on profitability, and 27 percent more likely to have excellent economic profit margins.

- Companies with the same ranking for having ethnically and culturally diverse executive teams were 33 percent more likely to lead their industry on profitability. The report further suggested that including other diverse people, such as people with international experience, individuals from different ages, and members of the LGBTQ+ community, could enhance the company’s bottom line.

Regarding LGBTQ+, research shows that companies are embracing diversity among that population. For the first time, 686 of the nation's leading companies and law firms earned a perfect score of 100 for their LGBTQ policies and practices, according to the Human Rights Campaign Foundation’s 2020 Corporate Equality Index (CEI), which measures inclusion in the workplace. Those organizations had an estimated $12 trillion in revenue, with 12.4 million workers in the United States and 11.9 million around the world, according to the CEI.

Multicultural buying power

Another way to make the business case for diversity is to research and understand the economic impact that people of color -- Hispanics, Blacks, Asians, and Native Americans -- make on society through their buying power. In the Multicultural Economy (2018), Jeffrey M. Humphreys of the Selig Center for Economic Growth defines buying power as after-tax personal income for all spending, excluding money borrowed or previously saved. The combined buying power of these racial and ethnic groups was projected to grow faster than the white market.

Humphreys suggested that “as the U.S. consumer market becomes more diverse, advertising, products, and media must be tailored to each market segment” (p. 4).

- Hispanic buying power is projected to be $1.9 trillion by 2023. Mexicans are the largest subgroup and represent over half of the buying power, followed by Puerto Ricans, Central Americans, South Americans, and Cubans.

- Black buying power is estimated to be $1.5 trillion by 2023. Part of that has to do with more Blacks becoming more educated, which could result in higher-paying occupations, according to Humphreys. Because they are much younger, Black consumers increasingly are seen as trendsetters for teens and young adults.

- Asian buying power is forecasted to be $1.3 trillion by 2023, Chinese (except Taiwanese) are the largest subgroup but are second to Asian Indians in buying power, followed by Filipino, Korean, and Vietnamese people. Chinese are the largest subgroup of Asians, who are younger and better educated than the average American.

- Native American buying power is predicted to be $136 billion by 2023.

In summary, Hispanics’ buying power will account for 11.2 percent of the U.S. total, while the combined buying power of Blacks, Asians, and Native Americans is expected to account for 17.5 percent.

Starbucks and Black Lives Matter

Angela Chitkara (2019) noted that millennials and Y and Z generations want to work for diverse, inclusive companies that make meaningful contributions to society. In the age of activism and cancel culture, where reputation is no longer a non-financial asset, a brand’s actions must align with its values, Chitkra explained.

Amid protests in summer 2020 demanding justice after the murders of George Floyd, Breanna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and others, many brands began posting Black Lives Matter statements on social media and donating money to social justice organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Starbucks is an example of a brand where its actions and values came into question during this period of unrest. The coffee chain tweeted, “Black lives matter. We are committed to being a part of change.” Shortly thereafter, Starbucks faced backlash because it would not allow employees to wear Black Lives Matter attire or accessories, fearing the political message could be misunderstood, the New York Times reported. Starbucks lists “acting with courage, challenging the status quo and finding new ways to grow our company and each other” as one of its four values.

Employees and customers quickly pointed out that Starbucks handed out LGBTQ pins and T-shirts during Pride Month. Then a #BoycottStarbucks hashtag emerged, MarketWatch reported. Starbucks soon backpedaled and partnered with its Black Partner Network and Black Starbucks leaders to make available a quarter of a million Starbucks-branded Black Lives Matter T-shirts.

It also donated $1 million in neighborhood grants to promote racial equity and inclusion. Other initiatives include a To Be Welcoming online curriculum that addresses bias.

“Starbucks stands in solidarity with our Black partners, community and customers, and understand the desire to express themselves. This is just one step in our journey to make our company and our communities more inclusive,” according to a company statement.

This was not the first time Starbucks has faced flak for race-related issues. In 2015, the coffee chain came under fire for asking its baristas to write “Race Together” on cups and engage in conversation with customers about race. The initiative arose after the murders of Michael Brown and Eric Garner and resulting unrest. The effort flopped because Starbucks didn’t spend enough time "discussing how it would look for a white billionaire to front a national dialogue on race," a Black woman who is a Starbucks board member told Fast Company.

Chitkara concluded that “the lack of strategic integration of Diversity and Inclusion efforts poses significant business and reputation risks to an organization, as social issues become a greater focus for investors, partners, customers and employees” (p. 40).

Discussion Questions

- Are brands such as Starbucks supporting Black Lives Matter because it aligns with its values or because it could help improve their profits? Explain.

- How well did Starbucks’ stated value align with its actions in 2015 and 2020?

Retaining Diverse UK Public Relations Practitioners

Public relations practitioners of color in the United Kingdom experience similar workplace issues as their counterparts in the United States.

For example, the CIPR Race in PR report (2020) found these key themes: Racism and microaggressions. A microaggression is “a statement, action, or incident regarded as an instance of indirect, subtle, or unintentional discrimination against members of a marginalized group such as a racial or ethnic minority” (p. 14). One of the 17 BAME practitioners interviewed stated:

“I once mentioned to a white colleague that I went to a private school and his response was, how did your parents afford that? That’s an example of a microaggression, people assuming that because you are black that you come from a deprived background” (p.15).

Inflexible and noninclusive culture. This includes pressure to conform, moving in the right social circles, and cultural rigidity. Another public relations professional noted the following:

“It’s such a polished world in comms in London. You need to say the right things and speak the right way. I’m not posh at all, it has been years of tailoring my voice, the way I sound and act …. My dad is from Southeast Asia and my mum has a strong UK regional accent, so I didn’t sound or act like the people in this industry. I had to really work on it” (p. 16).

Lack of equal opportunities and progression. Next, this BAME practitioner echoed what many African American parents tell their children:

“My dad had always said to me ‘Son, you’ll have to work twice as hard to get what the white man has got’. He wasn’t wrong! It certainly has felt like that in PR” (p. 18).

Unconscious bias. Finally, this BAME professional mentioned a pejorative used to describe some African American women:

“As I’ve progressed I’ve come to realise that some, a minority, question my ability based on the colour of my skin. I also have a general sense, and some experience, of some people labelling Black women as aggressive when they are simply being assertive” (p. 20).

CIPR noted that although it did not discuss disability, sexuality, age, gender and social mobility, reported experiences mirror Race in PR report findings.

Diversity in the UK and PR Workplace

Public relations is practiced globally, but this section will focus solely on diversity in the United Kingdom (UK) because of a 2020 report titled “Race in PR: BAME lived experiences in the UK PR industry.” The UK consists of England, Wales, and two other countries. The UK uses the acronym BAME -- Blacks, Asian, and Minority Ethnic -- to classify ethnic groups who are not white.

In England and Wales, the white ethnic group is 86 percent, while the BAME population stands at 14 percent, according to the 2011 UK Census, the latest available updated in 2019. In London, however, BAMEs made up 40.2 percent of the population.

The London, England-based Chartered Institute of Public Relations, the largest group for public relations practitioners in the UK and overseas, acknowledges that the profession has a diversity problem.

In its Race in PR report (2020), CIPR found that the number of BAMEs has declined from 11 percent in 2015 to 8 percent in 2019. Similarly, CIPRs State of the Profession Report 2019 found that the public relations industry is becoming less diverse in terms of ethnicity and sexuality. Also, women still lag in leadership roles and pay.

Regarding ethnicity, 92 percent identified as white, an increase of over 86% in 2018, and 90% in 2017, CIPR explained. With sexuality, 89 percent identified as heterosexual, an increase of 4% from the previous year.

Furthermore, women made up 67 percent of the profession, but men held 44 percent of executive roles, the CIPR report states. However, the report found that the gender pay gap decreased from the previous two years.

Finally, in listing the top challenges facing the public relations industry, “lack of diversity amongst PR professionals” ranked No. 9 out of 11, according to CIPR.

“The PR industry agrees that diversity is important in attracting the best talent, to bring fresh thinking, creativity and insights, but our actions speak louder than our words,” Avril Lee MCIPR, CIPR Chair of the Diversity and Inclusion Network, writes in the 2019 report. “Without those inside changing the status quo, those outside will remain locked out and our profession will be poorer for it.”

Defining Gender

In addition to race and ethnicity, gender is one of “the big three” often discussed regarding diversity in the female-dominated public relations profession.

As race and ethnicity sometimes are used as synonyms, gender and sex also are confused. The Associated Press Stylebook notes that they are not the same.

“Gender refers to a person’s social identity, while sex refers to biological characteristics,” the AP stylebook points out, noting that everyone does not fall under these categories.

For example, a person’s sex can be male at birth, but their gender identity can be a woman.

Defining Race & Ethnicity

The number of people of color of various races and ethnicities is increasing in the United States, but not in the public relations profession. Let’s define race and ethnicity before exploring those figures. The words race and ethnicity sometimes are used interchangeably, but they are different.

Regarding race, Webster’s New World Collegiate Dictionary (WNWCD) notes that it refers to groups of people different from others “because of supposed physical or genetic traits.”

Race also can refer to groups of people united based on “common history, nationality, or geographic distribution,” WNWCD states. However, the dictionary points out that some scientists say that classifying race as biological is invalid.

Many scholars have asserted that race is a social construct, not a biological one. Sonya Nieto and Patty Bode (2018) wrote that differences are rooted in sociology, not biology because they are based on experiences within a cultural group.

“There is really only one race—the human race,” Nieto and Bode suggested. “Historically, the concept of race has been used to oppress entire groups of people for their supposed differences” (p. 36).

The U.S. Census Bureau’s definitions of race and ethnicity are based on how people identify themselves. A person can self-identify as two or more races. Race falls into five categories on the 2020 Census:

- White

- Black or African American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Asian

- Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.

“The race categories generally reflect social definitions in the U.S. and are not an attempt to define race biologically, anthropologically, or genetically,” according to the Census Bureau. “We recognize that the race categories include racial and national origins and sociocultural groups.”

Regarding ethnicity, WNWCD defines it as a person’s “cultural background or where they came from.” The Census Bureau states that ethnicity refers to whether a person is Hispanic, Latino, or not. It added that Hispanics and Latinos could be of any race.

Finally, Damion Waymer (2012) argues that ethnicity “typically refers to some mixture of race, religion, language, and/or ancestry”(p. 8).

Case Study: Kendall Jenner & Pepsi

Background

PepsiCo faced criticism in April 2017 with a short-film commercial starring then 21-year-old Kendall Jenner, a white model and reality TV star featured on “Keeping Up with the Kardashians.” The nearly 3-minute commercial was titled “Live for Now” and featured the song "Lions" by Skip Marley. The commercial aired on April 4, 2017, the 49th anniversary of the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Pepsi notes that consumers enjoy its products “more than one billion times a day in more than 200 countries and territories around the world,” according to pepsico.com. Pepsi points outs that “supporting diversity and engagement is not only the right thing to do, it is the right thing to do for our business.” The corporation also notes that it “embraces the full spectrum of humanity” by “building a more diverse, more inclusive workplace, and promoting what we call courageous engagement in our company and the communities we serve.”

The controversial commercial first depicts Jenner in a blonde wig, silver dress, and dark lipstick posing for photos while smiling people from diverse racial, ethnic and cultural backgrounds peacefully protest with signs reading “Join the Conversation” and “Love.” After a young man nods for Jenner to join in, she rips off her wig, wipes off her dark lipstick, and makes way through the crowd, now clad in a blue-jean outfit. In a pivotal moment, a smiling Jenner grabs a can of Pepsi and hands it to a police officer lined up in front of the protesters. The crowd cheers and the police officer smiles. The screen reads: "Live bolder. Live louder. Live for now.”

Dilemma

Many social media users accused Pepsi of being tone-deaf and trivializing the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement for financial gain. The Rev Dr. Bernice King, the youngest daughter of the late Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., tweeted, “If only Daddy would have known about the power of #Pepsi.” Civil rights activist and podcaster DeRay Mckesson, tweeted, “If I had carried Pepsi I guess I never would've gotten arrested. Who knew?”

BLM was founded in July 2013 after George Zimmerman, a white-Latino neighborhood watch captain, was found not guilty of fatally shooting Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old Black male, in Sanford, Florida, in February 2012. Since then, BLM has grown to 16 chapters, including 14 in the United States and the rest in Canada and the United Kingdom, according to blacklivesmatter.com.

The commercial debuted roughly nine months after over 100 BLM protests erupted after the July 2017 deaths of two Black men: Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on July 5 and Philando Castlle in St. Anthony, Minnesota, a day later. Police shot and killed both men.

Many people compared the image of Jenner handing the police officer a Pepsi to the real image of Ieshia Evans, a Black woman who stood silently in front of police during a protest in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on July 9. Police later arrested her.

The clip resurfaced in summer 2020 after protests erupted nationwide after the death of another Black man in Minnesota, George Floyd, who died May 25 after a police officer held his knee on his neck for nearly nine minutes.

The commercial was a “blatant example of white privilege,” senior style editor Kelsey Stiegman wrote in Seventeen magazine June 2020. “Kendall, a white, millionaire supermodel, may be able to safely engage with a police officer, but for a Black person, this harmless act could be a death sentence.”

Course of Action

A day after the commercial was released, Pepsi pulled the ad and issued the following statement:

“Pepsi was trying to project a global message of unity, peace and understanding. Clearly we missed the mark, and we apologize. We did not intend to make light of any serious issue. We are removing the content and halting any further rollout. We also apologize for putting Kendall Jenner in this position."

Five months later, Indra Nooyi, who was PepsiCo’s CEO at the time, told Fortune that when she saw that people were upset, she pulled the ad because she didn’t want to offend.

"This has pained me a lot because this company is known for diversity, and the fact that everybody who produced the commercial and approved the commercial did not link it to Black Lives Matter made me scratch my head," Nooyi told Fortune. "I had not seen that scene. And I take everything personally."

Jenner never publicly responded to the backlash. Instead, she spoke out about the matter six months later in the October 2017 season 14 premiere of “Keeping Up With the Kardashians.” Jenner said, “I would never purposely hurt someone ever. And I would, obviously, if I knew this was gonna be the outcome, like, I would have never done something like this. But you don’t know when you’re in the moment. I just felt so f—ing stupid.”

Consequences

According to BrandWatch, PepsiCo’s social media sentiment was 53.3 percent negative on the day the commercial appeared and 58.6 percent negative the next day. Additionally, MarketWatch reported that in 2016, PepsiCo’s brand value dropped by 4 percent. Researchers say the ad could have cost between $2 million and $5 million.

Moral of the Story

PepsiCo’s in-house team created the commercial, which suggests that the team needed more diverse perspectives. Hearing different sides could have been achieved by seeking input from or hiring an outside firm to develop the commercial. Others have suggested that the beverage-maker needed more planning and research with its consumers, or needed to get an external perspective, particularly from protesters and activist groups. In summary, sometimes trying to save money on the front end is not worth the cost to an organization’s reputation on the back end.

Organizations must choose the right spokespersons who have authenticity and integrity. They also must seek outside opinions.

Discussion Questions

- How does this case connect back to what you have learned about the principle of requisite variety?

- Other than issuing an apology, what other course of action could PepsiCo have taken?

- How well did Pepsi live up to its diversity and engagement statement?

Works Cited

About the company. (n.d.). PepsiCo, Inc. Official Website. https://www.pepsico.com/about/about-the-company

CBS This Morning. (2016, July 15). Woman in iconic Baton Rouge standoff photo breaks silence [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LFC6l0DjDF0

Cady Lang. (2017, October 2). Kendall Jenner cried while addressing Pepsi ad backlash. Time. https://time.com/4965293/kendall-jenner-cries-addresses-pepsi-ad-backlash/

Carlos. (2017, April 5). Kendall Jenner for Pepsi Commercial [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j9x15lR9VIg

Diversity and engagement. (n.d.). PepsiCo, Inc. Official Website. https://www.pepsico.com/about/diversity-and-engagement

Hobbs, T. (2019, July 26). Pepsi’s ad failure shows the importance of diversity and market research. Marketing Week. https://www.marketingweek.com/pepsi-scandal-prove-lack-diversity-house-work-flawed/?nocache=true&login_errors%5B0%5D=empty_username&login_errors%5B1%5D=empty_password&_lsnonce=e170cca5a5&rememberme=1

Joyce, G. (2017, April 7). Data on the extent of the backlash to the Kendall Jenner Pepsi ad. Brandwatch. https://www.brandwatch.com/blog/react-kendall-jenner-pepsi-ad/#:~:text=Within%20the%20most%20common%20reactions,social%20movements%20for%20commercial%20gain

Pepsi statement re: Pepsi moments content. (2017, April 7). PepsiCo, Inc. Official Website. https://www.pepsico.com/news/press-release/pepsi-statement-re--pepsi-moments-content04052017

Victor, D. (2017, April 5). Pepsi pulls ad accused of trivializing Black Lives Matter. The New York Times - Breaking News, World News & Multimedia. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/05/business/kendall-jenner-pepsi-ad.html

Wright, I. (2017, April 10). 3 lessons brands should learn from Pepsi's Kendall Jenner ad disaster. PRNEWS. https://www.prnewsonline.com/pepsi-ad-kendall

Pepsi statement re: Pepsi moments content. (2017, April 5). PepsiCo, Inc. Official Website. https://www.pepsico.com/news/press-release/pepsi-statement-re--pepsi-moments-content04052017

Stiegman, K. (2020, June 1). Fans slam Kendall Jenner for not addressing police brutality after clips from Pepsi commercial resurface. Seventeen. https://www.seventeen.com/celebrity/a32729598/fans-slam-kendall-jenner-for-not-addressing-police-brutality-after-pepsi-commercial-clips-resurface/

Taylor, K. (2017, September 21). Pepsi CEO reveals her surprising response to controversial Kendall Jenner ad. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/pepsi-ceo-defends-kendall-jenner-ad-2017-9

International and Global Public Relations

International public relations refers to the practice of public relations that occurs across

international boundaries and cultures. This type of public relations occurs when an organization and its publics are in different countries.

International public relations takes a local approach by focusing on differences among publics and audiences, while global public relations takes a global approach that focuses on similarities (Alaimo, 2017).

First, with international public relations, PR practitioners “implement distinctive programs in multiple markets, with each program tailored to meet the often acute distinctions of the individual geographic market” (Anderson, 1989, p. 413). This relates to the local approach, which states that “different countries and cultures are so different that they require strategies that are specifically designed to respond to local opportunities and challenges” (Alaimo, 2017, pp. 3-4).

Second, global public relations “superimposes an overall perspective on a program executed in two or more national markets, recognizing the similarities among audiences while necessarily adapting to regional differences” (Anderson, 1989, p. 13). This relates to the global approach, where practitioners "believe that there are certain best practices and messages that are generally successful across countries and cultures” (Alaimo, 2017, pp. 3-4).

An example of the local vs. global approach occurred in 2012 when IKEA, a Swedish furniture company, decided to airbrush a woman out of a catalog it would use in Saudi Arabia because women had to cover their faces and bodies to appear in public (Alaimo, 2017). IKEA apologized after the trade minister of Sweden, a country that advocates for women, complained. The company faced a conundrum in deciding whether to develop content specific to the Saudi culture or project a shared global identity.

Discussion questions

- One public relations scholar, Krishnamurthy Srimamesh (2009) has argued that there is no need to separate the term global public relations from international publications “because even ‘domestic’ publics are becoming multinational and multicultural due to globalization." What is your position on this topic?

- Rather than airbrushing the woman out of the catalog, what else could IKEA have done that would have been cost-effective? How does your suggestion relate to the global or local approach?

Multicultural and Global Public Relations

In 1995, Stephen Banks defined multicultural public relations as “the successful negotiation of multiple meanings that result in positive outcomes in any communication activity” (p. 42). Five years later, the author improved his definition to take diversity into consideration.

Banks (2000) wrote: “Multicultural public relations can be defined as the management of formal communication between organizations and their relevant publics to create and maintain communities of interest and action that favor the organization, taking full account of the normal human variation in the systems of meaning by which groups understand and enact their everyday lives."

Multicultural public relations helps the profession see diversity as part of its daily practice that connects with an organization’s values, according to Dean Mundy (2016). The multicultural perspective also removes the “western-centric, corporate-centric lens” and helps an organization forge meaningful relationships with diverse stakeholders.

While some public relations scholars have separate definitions for each approach to public relations, Juan-Carlos Molleda and Sarab Kochhar (2019) combined the definition of global and multicultural public relations:

“A strategic and dynamic process that cultivates shared understanding, relationships, and goodwill among organizations and a combination of their culturally heterogeneous home, host, and transnational stakeholders, with the aim of achieving and maintaining a consistent reputation and established legitimation.”

Molleda and Kochhar note that all types of organizations practice global and multicultural public relations, including government and nongovernmental organizations and agencies. The authors also note that public relations programs become more complex when organizations operate across borders.

Approaches to Worldwide Public Relations Practice

Public relations practitioners can use different approaches to reach diverse stakeholders across the globe. Some of these approaches include multicultural public relations, global public relations, and international public relations. These approaches differ from domestic public relations because they must take cultural differences and dimensions into consideration.

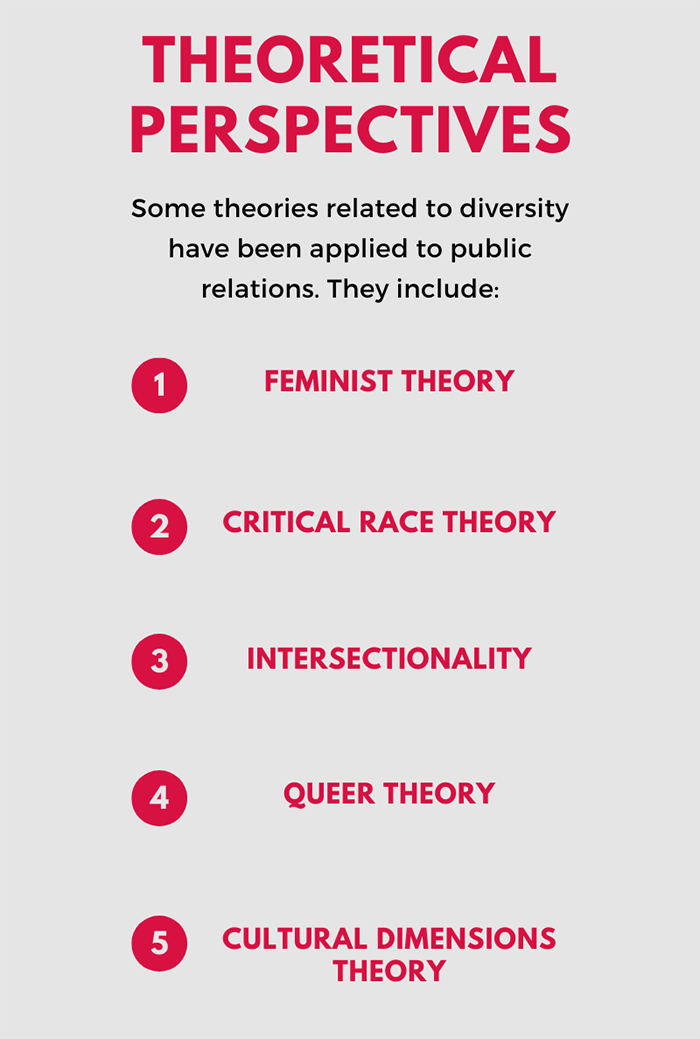

Cultural Dimensions Theory

Geert Hofstede (2001), a Dutch social psychologist, developed six cultural dimensions based on his research with IBM in 40 countries.

Hofstede defines culture as “the programming of the human mind by which one group of people distinguishes itself from another group.”

The six dimensions are:

- Power distance

- Individualism/collectivism

- Masculinity/femininity

- Uncertainty avoidance

- Short-term/long‐term orientation

- Indulgence/restraint

The initial version of the cultural dimensions theory included only the first four dimensions (Hofstede, 1984).

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory is used in global public relations to understand cultural nuances to craft, strategies, tactics, and messages that resonate with target publics, according to Juan-Carlos Molleda and Sarab Kochhar (2019). The authors cautioned that the following characteristics of the six cultural dimensions “can vary within a country where the urban meets the rural, and where the dominant culture meets a variety of subcultures.”

First, high power distance cultures, such Russia and China, value hierarchy; respect is given, rules are followed, and status symbols are valued, according to Kara Alaimo (2017). Low power distance cultures, such as Sweden, where fashion retailer H&M is based, is more egalitarian, and it is acceptable to question your boss, Alaimo notes.

Second, in individualistic cultures, such as the United States, people see themselves as distinct from others and put the interests of themselves and their immediate family first. The majority of the world’s cultures are collectivistic; China is an example of a society that values relationships and will put their extended families and organizations first.

Third, in masculine cultures, such as Japan, men are expected to be assertive, competitive, and driven by salary, status, and success. Women are expected to be caring, unassuming, and focused on quality of life. In feminine cultures such as Norway, both men and women are supposed to embody the “emotional gender roles” associated with women in masculine cultures.

Fourth, uncertainty avoidance refers to the level of comfort people in this culture feel when matters are ambiguous, unknown, or unclear. Low uncertainty avoidance cultures such as the United States internalize stress and emotions and are OK with few rules. High uncertainty avoidance cultures, such as Greece, worry more and must have formalized, precise instructions.

Fifth, cultures with long-term orientation, such as parts of Asia, focus on future rewards and respect thrift and tradition. In contrast, cultures with short-term orientation, such as Australia, are more focused on the past and present and expect to see immediate rewards and results from their efforts.

Sixth, in high indulgence cultures, such as Mexico, people are healthier, happier, and hopeful about the future. On the other hand, low indulgence cultures, such as Pakistan, are pessimistic and less optimistic.

Queer Theory

Queer theory challenges the perspective that heterosexuality is the norm and argues against stereotypes, categorizing sexuality, and labeling someone’s identity. Queer theory originated in 1990 with Italian feminist Teresa de Lauretis.

Natalie T.J. Tindall and Richard Waters (2012) applied queer theory by interviewing gay male public relations practitioners. The study marked the first time the approach had been used in a real-world setting beyond textual and literary analysis, which helped substantiate some of queer theory’s claims.

Tindall and Waters point out that queer theory adds value to research about avowed and ascribed identities, disavows stereotypes, and acknowledges differences. They argue that applying queer theory to public relations can help achieve excellence theory’s concept of diversity and requisite variety. It also can help with recruitment and retention; help an organization accept the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community; and improve the organization’s bottom line.

Intersectionality

Intersectionality maintains that people have multifaceted social identities rather than one isolated identity that makes their lived experiences unique. Kimberlé Crenshaw, a law professor and Black feminist, coined the term intersectionality in 1989. The author wrote about how systems of power oppress Black women at work and in their everyday lives.

Jennifer Vardeman-Winter and Natalie T.J. Tindall (2010) argue for a theory of intersectionality in public relations for two reasons:

1) simply explaining diversity and difference through the concept of requisite variety lacked complexity; and 2) as responsible advocates for their clients, public relations practitioners cannot simply reduce publics to psychographics and demographics.

Vardeman-Winter and Tindall (2010) further argue that intersectionality in public relations can be analyzed on nine levels: intra-industrial, organization-publics, publics and community, representational, media, multinational/global, theoretical, and pedagogical.

Finally, the scholars further note that intersectionality operates on various levels that can oppress some groups for the privilege of others.