Lesson 1: Understanding Ethics & The Profession

This lesson is an introduction to public relations ethics. We begin by defining what we mean when we use the word "ethics."

Ethics matter. The lapse of ethics in many of the leading institutions has produced a global decline in trust. As public relations is an industry that relies on trust to build mutually beneficial relationships, ethical fortitude is a paramount concern as evidenced by the growing body of scholarship focused on the establishment and use of ethical decision-making models. There have been several theories and ethical decision-making models proposed which provide great value to the public relations profession.

First, however, it is important to understand what is meant when using the term ethics. Simply put, ethics are a process of determining right from wrong. Heath and Coombs suggest that proper ethical choices will “foster community by creating, and maintaining mutually beneficial relationships.”

Next Page: Understanding Ethics As a Decision-Making ProcessUnderstanding Ethics As a Decision-Making Process

One of the challenges often faced when discussing ethics is the concept that it is synonymous with morality. Ethicist Scott Rae tackles this common misunderstanding by suggesting the following:

Most people use the terms morality and ethics interchangeably. Technically, morality refers to the actual content of right and wrong, and ethics refers to the process of determining right and wrong. In other words, morality deals with moral knowledge and ethics with moral reasoning. Thus, ethics is both an art and a science.

Put another way, morality is knowing the difference between right and wrong, whereas ethics provides a system to understand right and wrong. People can use ethics in order to reason through situations and arrive at courses of actions. Ethics, however, are not simply a set of rules or a set of “if –then” statements that will automatically ensure public relations professionals behave ethically. Rather ethics is the art and science of the process used to arrive at a decision, based in a deeper conviction. The deeper conviction rests in one’s understanding of the industry, the duties to that industry, the virtues of the industry and one’s personal moral framework. How one understands those convictions, or morals, is crucial to ethical reasoning.

It probably does not surprise you to learn that some people suggest public relations professionals are ethically obligated to select choices that involve “doing the right thing.” But what is the right thing? The study of ethics helps identify the process public relations professionals use in order to make decisions about what course of action is the right one to take.

Ethical Theories

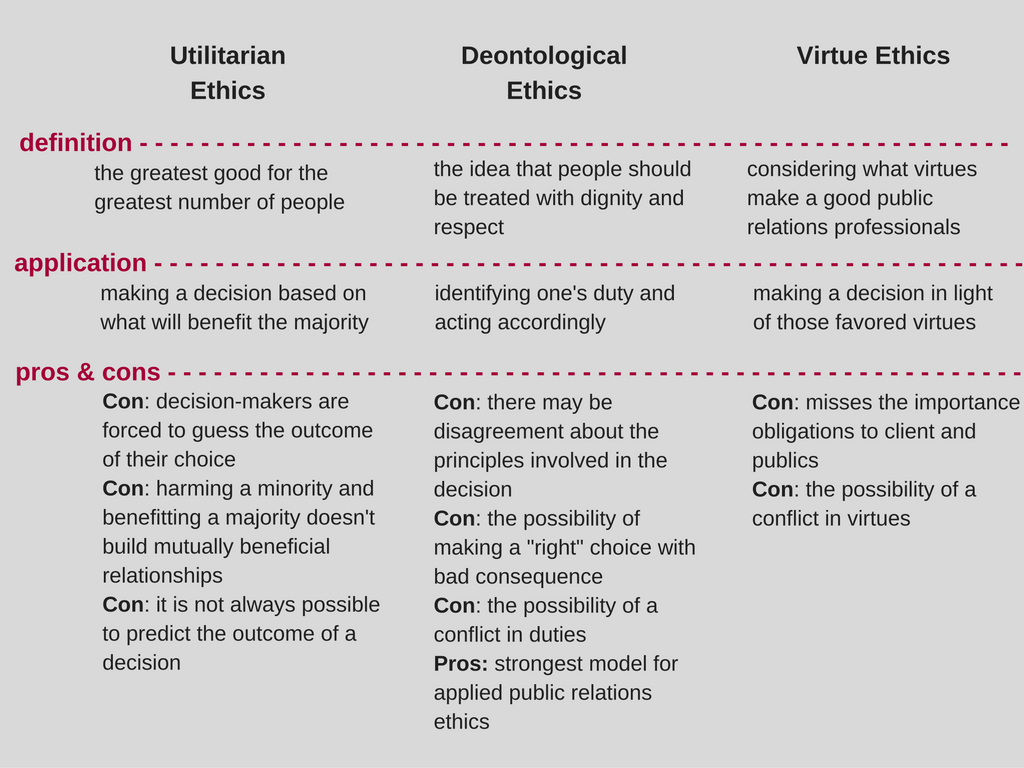

As mentioned previously, Rae suggests that ethics are a process that is both an art and a science. There are generally three philosophical approaches, or what may be considered the science, to ethical reasoning:

- utilitarian ethics

- deontological ethics

- virtue ethics

When people talk about these areas, they are usually discussing an area of ethics known as normative ethics, or the process of considering and determining ethical behavior.

Utilitarian Ethics

The first ethical system in normative ethics, utilitarianism, is often equated with the concept of “the greatest good for the greatest number.” The idea is that ethical decisions are made based on the consequences of the action, which is why it is also sometimes called consequentialism. Interestingly, Curtin, Gallicano and Matthew found that, when faced with ethical situations in public relations, “Millennials will use utilitarian reasoning to avoid confrontation and achieve consensus.” The attraction of this ethical perspective may lie in the fact that it appears to be a way to weigh out the impact of behavior and determine the greatest good for the greatest number.

While this idea initially may seem appealing, particularly with a field that has a core duty to the public, it does not provide a solid ethical framework for decision-making. There are three main concerns that seem to arise when public relations professionals rely on utilitarian ethics to make decisions.

First, rather than looking at the choice or action itself, decision-makers are forced to guess the potential outcomes of their choice in order to determine what is ethical. Grunig believes this is a faulty line of reasoning when he suggested that: “We believe, in contrast, the public relations should be based on a worldview that incorporates ethics into the process of public relations rather than on a view that debates the ethics of its outcomes.” In other words, ethics should be about the decision-making process, not just the outcome, which can’t be guaranteed.

Second, utilitarian ethics also “presents questions of conflict with regard to which segment of society should be considered most important” in weighing the “good” or outcome. In other words, if a solution drastically harms a minority group, would it be ethical if the majority benefited from that decision? This seems to contradict the goal of public relations to build mutually beneficial relationships, regardless of the number of people in a particular stakeholder group.

The third objection is that it is not always possible to predict the outcome of an action. Bowen points out that “consequences are too unpredictable to be an accurate measure of the ethics of a situations.” In other words, consequences of actions can be highly volatile or impossible, even, to predict. Using outcomes as a measurement of ethics will not, therefore, provide an accurate way for professionals to measure whether decisions are ethical. Professionals must be able to evaluate decisions and choices with concrete ethical guidelines instead of hoping that certain outcomes will result in them having made an ethical choice.

Many scholars in public relations identify these issues, as well as others, as evidence that utilitarianism, sometimes called consequentialism due the concept relying on the consequence of a decision, is not as strong of a fit for public relations professional ethics.

Deontological Ethics

The second prominent concept, deontological ethics, is associated with the father of modern deontology, Immanuel Kant. He was known for the ‘Categorical Imperative’ that looks for transcendent principles that apply to all humans. The idea is that “human beings should be treated with dignity and respect because they have rights.” Put another way, it could be argued that in deontological ethics “people have a duty to respect other people’s rights and treat them accordingly.” The core concept behind this is that there are objective obligations, or duties, that are required of all people. When faced with an ethical situation, then, the process is simply one of identifying one’s duty and making the appropriate decision.

The challenges to this perspective, however, include 1) conflicts that arise when there is not an agreement about the principles involved in the decision; 2) the implications of making a “right” choice that has bad consequences; and 3) what decisions should be made when duties conflict. These challenges are definitely ones that should be considered when relying on this as an ethical system.

However, despite these concerns, many have found that deontology provides the strongest model for applied public relations ethics. Bowen, for example, suggests that “deontology is based on the moral autonomy of the individual, similar to the autonomy and freedom from encroachment that public relations seeks to be considered excellent. That ideological consistency gives the theory posed here a solid theoretical foundation with the practice of public relations as well as a normative theory function.” Similarly, Fitzpatrick & Gauthier suggest, “practitioners need some basis on which to judge the rightness of the decisions they make everyday. They need ethical principles derived from the fundamental values that define their work as a public relations professional.” A key thought in this concept is the assumption that there needs to be some objective morals that professionals rely on in order to determine ethical behavior.

Virtue Ethics

Finally, a third and growing area of philosophical reasoning with ethics is known as virtue ethics, one that has gained more attention in public relations scholarship in recent years. This philosophy stems from Aristotle and is based on the virtues of the person making a decision. The consideration in virtue ethics is essentially “what makes a good person,” or, for the purpose of this discussion, “what makes a good public relations professional?” Virtue ethics require the decision-maker to understand what virtues are good for public relations and then decisions are made in light of those particular virtues. For example, if the virtue of honesty is the of utmost importance to a good public relations professional, then all decisions should be made ethically to ensure honesty is preserved.

While this theory is growing in popularity, there are several objections that can be made. First, in terms of the public relations profession, the focus on virtues of the professional themselves seems to miss the importance and role of obligations to clients and publics. The industry is not simply about what public relations people do themselves, but ultimately the impact to society. Additionally, it also can face the same obstacle as deontological ethics when having conflicting virtues. If there is a virtue of loyalty to a client and honesty to the public, what happens when they conflict? To which one should a professional defer?

These three theories of ethics (utilitarian ethics, deontological ethics, virtue ethics) form the foundation of normative ethics conversations. It is important, however, that public relations professionals also understand how to apply these concepts to the actual practice of the profession. Ethical discussion that focuses on how a professional makes decisions, known as applied ethics, are heavily influenced by the role or purpose of the profession within society.

Ethical Decision Based On Definition

Public relations is an industry that requires ethical behavior and yet is often criticized as one that has incredible ethical lapses. In spite of this, some claim that public relations professionals should have “unimpeachable ethical standards” that develop trust from clients and the public. The reason people argue that ethical behavior is inherent to public relations relates directly to the purpose and function of public relations in society.

Four Standards of a Profession

To be a recognized profession in society, there are four standards that must be met:

- membership in an occupational organization

- special expertise

- a service orientation

- autonomy

Public relations professionals meet each of these criteria and are, therefore, held to expectations that society has of professionals. Part of society’s expectation of professionals is that they will not place personal gain ahead of the public good. As a result of this expectation, “society grants professional standing to those groups which contribute to the well-being of the broader society.”

The contribution to society could be considered the moral purpose of the profession. Seib and Fitzpatrick suggest:

“Every profession has a moral purpose. Medicine has health. Law has justice. Public relations has harmony—social harmony.”

In other words, it is this professional responsibility for public relations that helps professionals understand what their ethical obligation is in various situations. For example, it is reasonable to expect ethical decisions of a doctor to be based on their obligation as a medical professional. We do not expect lawyers or teachers to have the same ethical decision-making and moral obligations as they belong to a different industry that has different requirements, standards and purposes. Therefore, each industry must be fully understood in order to articulate the moral obligations and ethical decision making required. This makes the definition or essence of public relations particularly pertinent to the discussion of ethics, as it is the foundation for the ethical decision-making expected of professionals within the profession.

Assumptions of Obligations in the Public Relations Profession

In the quest to define the nature of public relations, people have developed various perspectives on what the role of public relations is within society. Comparing the asymmetrical and symmetrical perspectives of public relations, the two most prominent views in today’s scholarship and practice today, Grunig says this of the asymmetrical perspective:

Public relations is a way of getting what an organization wants without changing its behavior or without compromising. It is an alluring mind-set for most organizations. All one has to do to get what one wants is to hire a public relations person who will make you look “competent, effective, worthy or respect-powerful,” even if you are not.

He goes on to champion the symmetrical perspective, suggesting that “we believe that excellent public relations departments adopt the more realistic view that public relations is a symmetrical process of compromise and negotiation and not a way for power.” He argues that those who do hold to the asymmetrical perspective define “public relations as the use of communication to manipulate publics for the benefit of the organization.” This belief may lead some practitioners to “convince themselves that they are manipulating publics for the benefit of those publics.”

.png)

Obligations to the Organization

This contention over the fundamental nature and purpose of public relations may be what has led to a confusion of obligations for professionals in public relations. If the fundamental purpose of public relations is, for example, to coerce publics into specific behaviors for the good of the company, ethical decision making will be drastically skewed to the benefit, perhaps at all costs, of the organization who retains a public relations professional. If, however, as Grunig and many others suggest, public relations is fundamentally about serving both the organization and the public, pursuing mutual understanding and adjustment for the benefit of all parties, ethical reasoning takes on a very different shape. This is the point Fitzpatrick & Gauthier make when they claim:

Public relations professionals—as professionals—have obligations that extend beyond the profitability (however defined) of the organization represented. Responsibility to the public—or in the case of public relations, to multiple publics—must be balanced with responsibility to the client or employer.

Obligations to the Public

It is clear that public relations professionals need to have a perspective of the industry that accounts for ethical obligations both to the client as well as the public. Perspectives that limit public relations to solely serving an organization result in hindering ethical reasoning among professionals. In order to address this concern, some suggest that the primary duty a public relations professional has is to the organization but publics are still served through developing social responsibility initiatives within an organization. However, even if a practitioner is seeking to define their ethical responsibility as being a voice for social responsibility within the organization, it is still “limiting in the effort to develop standards of practice in public relations because the primary focus is on the obligations of institutions rather than on the ethical obligations of public relations professionals.” In light of this, while some debate still remains within public relations about the nature of public relations, many people suggest that the industry is one of mixed-motives, with a commitment to the client as well as the public.

Obligations to the Practice

Finally, a third duty beyond the public and company the professionals in public relations must consider when making ethical decisions relates to the profession itself. A commitment to the wellbeing of the profession among those who practice public relations is what has led to the suggestion that it would be possible, though challenging, to create a universal code of ethics. If it is possible to identify unifying duties or professional values based on the nature of public relations, then it may be possible to develop a code of conduct. Moyer suggests that ethical lapses impact not only the individual professional but also the entire field of public relations. If this is the case, it would seem reasonable that those who choose to enter the profession bear some responsibility to the profession as a whole to uphold its standards and values.

Developing an Ethical Profession

In efforts to unify the profession, create standards of ethical behavior and reasoning, and to support trust from society and clients in the profession itself, public relations associations and codes of conduct have been developed. Associations like the Public Relations Society of America, the International Public Relations Association, and many others have developed standards of practice for those in membership. In addition, codes of conduct have been created to help guide professionals in the process of ethical behavior and practice. As mentioned previously, it has been argued that the profession may be reaching a point where a universal code of ethics could be adopted.

While associations and codes of ethics have provided a strong foundation toward helping the profession, there are limits to these efforts. For example, public relations is not an industry that is regulated by any group. In other words, a person may practice public relations without joining any of the professional associations or agreeing to abide by any code of ethics. In addition, even among those who do join the associations or sign on to codes of conduct, there is very little consequence when ethical behavior contradicts the association’s standards or code of conduct. There is no revoking of privileges that would prohibit continued practice in the profession, like there may be in the medical or legal profession.

Despite these limitations, associations and codes of conducts provide valuable education for professionals who are committed to the profession and ethical behavior. In addition, these associations are incredibly valuable in helping society understand what the practice of public relations should be and how it should function in ethically ambiguous situations. As we continue to grow as a profession, we may see continued emphasis on a universal code of conduct or ethical standards that ought to apply to all professionals in public relations.

Case Study: Facebook & Burson-Marsteller “Smear Google” Campaign

Background

This lesson has addressed the purpose of ethics being the process of determining right from wrong, and the applied ethical obligations of public relations professionals based on the place we hold in society. As mentioned in lesson one, some suggest that the moral purpose of public relations is to create social harmony. With this in mind, the now infamous case of Facebook hiring the well-known public relations firm, Burson-Marsteller to develop a smear campaign against Google poses some very intriguing ethical questions.

Dilemma

In the ever-growing digital landscape, Facebook and Google have become well-known rivals of each other. In early 2011, Facebook opted to run a campaign designed to highlight negative components about Google. They recruited Burson-Marsteller to pitch the stories to journalists and high-profile technology companies, focusing on Google’s Social Circle, which tracks data activity through social media of Google users. Burson-Marsteller pitched the story without disclosing who their client was and “even offered to help an influential blogger write a Google-bashing op-ed, which it promised it could place in outlets like The Washington Post, Politico, and The Huffington Post.”

Course of Action

When the story broke in the media, there was strong criticism of both Facebook and Burson-Marsteller for what many deemed to be a “smear” campaign. Facebook responded in an official statement saying:

"We engaged Burson-Marsteller to focus attention on this issue, using publicly available information that could be independently verified by any media organization or analyst. The issues are serious and we should have presented them in a serious and transparent way."

Perhaps the most interesting part of this case study, from the perspective of public relations ethics, is why a leading public relations firm would participate in a campaign of this nature. In response, the chief executive of the Public Relations Society of America, Rosanna Fiske, issued a statement to address these ethical concerns. She focused on the lack of disclosure as being a deceptive practice that violated the PRSA code of conduct. In addition, she pointed out that when deception is used as a core part of delivering a message, the public begins to question everything ever communicated: "When you are following misleading practices, the message is tainted," she said. Consumers "wonder what else have they done that perhaps I shouldn't trust."

Consequences

Echoing the general consensus of unethical practices, Burson-Marsteller eventually parted ways with their client, Facebook. Reflecting on the situation, a spokesperson for the agency said Facebook:

"requested that its name be withheld on the grounds that it was merely asking to bring publicly available information to light." But, he added, doing that was "not at all standard operating procedure and is against our policies, and the assignment on those terms should have been declined.”

Moral of the Story

In conclusion, this is a classic case example of the reason public relations professionals need to ground their practice in sound ethical decision making. In an industry with mixed-motives, serving clients, the public, and the profession, individuals must practice public relations with the highest levels of integrity and ethics in order to maintain trust.

Works Cited

Fowler, G. A. and Efrati, A. (2011, May 13). Facebook Hired PR Firm to Target Google. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from: http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748703730804576319351012761800

Krietsch, B. (2011, May 12). Burson-Marsteller and Facebook part ways. PR Week. Retrieved from: http://www.prweek.com/article/1264310/burson-marsteller-facebook-part-ways

Lyons, D. (2011, May 12). BUSTED: It Was FACEBOOK That Hired A Former CNBC Reporter To Spread Lies About Google. The Daily Beast. Retrieved from: http://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-google-lies-2011-5

Olivarez-Giles, N. and Guynn, J. (2011, May 12). Facebook paid PR firm to pitch journalists negative Google stories. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from: http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/technology/2011/05/facebook-admits-to-hiring-pr-firm-burson-marsteller-to-pitch-journalists-bloggers-to-write-negative-.html

For Discussion

Consider the following questions and prepare answers for discussion in your class.

Short Answer

Please provide a one to two paragraph answer to the following questions:

- Describe what is meant by the concept that public relations is one of mixed-motives.

- Define the purpose of public relations ethics.

- Describe what Seib and Fitzpatrick mean when they suggest that social harmony is the moral purpose of public relations.

Case Study Application Questions

Please answer the following questions after reading the one-page case study provided with this lesson.

- If you were working with Burson-Marsteller and were asked what you would recommend when Facebook requested a campaign like this, what would your answer be? As part of your response, be sure to address ethical obligations of public relations professionals and the role of public relations within society.

- What do you perceive to be the implications in society for public relations when situations like the case of Facebook and Burson-Marsteller occur?