Lesson 1: Native Advertising

Native advertising is defined as “any paid advertising that takes the specific form and appearance of editorial content from the publisher itself,” (Wojdynski & Evens, 2016, p. 157). In essence, native advertising is the use of advertisements which are disguised as authentic content. Fullerton, McKinnon, and Kendrick (2020) define fake news as content that is intentionally misleading, sensationalized, or deliberately false.

Native advertising mimics the look and feel of authentic content and falls under the umbrella of fake news.

One of the most common forms of native advertising is that of sponsored content. Ikonen, Luoma-aho, and Bowen (2016) describe sponsored content as a hybrid between advertising and journalism. Companies pay content providers to create articles which paint their product, service or idea in a positive light and then place those sponsored articles within the context of the independently written editorial medium. “It is about creating content that is so appealing that the potential customer wants to enjoy it, unlike advertising which is generally just disliked and skipped” (Lehto & Moisala, 2018, p. 3).

For sponsored content to be successful, the articles must look real. However, because the advertisements look like real articles, the audience may be deceived into thinking it is a credible editorial, not an advertisement (Schauster, Ferrucci, & Neill, 2016).

Next Page: TrustTrust

Persuasive communicators should consider ethical issues on both the macro and micro levels. Without considering the ethical impact, the overall distrust of communicators may increase. Baker and Martinson (2001) explain that the public exhibits distrust in communicators “because they fear those in the field do not respect them as individuals and are interested only in achieving immediate and narrowly defined self-interest goals or objectives” (p. 165).

To build trust with the community and to get the most out of persuasive messaging is of high importance to communicators. It is to the benefit of public relations professionals, the organizations they represent, and society as a whole to consider ethical issues when crafting native advertisements.

Disclosure

Wojdynski and Evans (2016) pinpoint two distinct factors that are required for successful disclosure of sponsored content. First, consumers must notice the disclosure itself. Second, consumers must comprehend what that disclosure means in reference to the content they engaged with.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) mandates every paid post be disclosed with language such as “#ad,” “sponsored content,” and “paid content.” It further demands that disclosures be:

- In clear and unambiguous language

- As close as possible to the native ads to which they relate

- In a font and color that’s easy to read

- In a shade that stands out against the background

*for more information regarding FTC native advertising disclosure go here

However, it is important to note that law and ethics are not the same. Law stresses what you must do, while ethics considers what you ought to do.

Disclosure language can impact an individual’s ability to correctly identify the content as advertising. With a variety of disclosure language utilized, consumer confusion and their inability to correctly identify native advertising may occur even when disclosure is present. Disclosure language that has been tested to have the greatest correct identification include: “paid ad,” “paid content,” “this content was paid for by,” “paid post,” and “ad” (Hyman et al., 2017). While other terms such as “brand voice” have been used by online publishers such as Forbes, they are not as readily identified as native advertising (Moore, 2014). Disclosure language, size and placement is important in signaling to the reader what they are viewing is an advertisement.

Disclosure (continued)

One thing to note when discussing disclosure placement is the concept of banner blindness. Banner blindness occurs when a web user overlooks what they perceive to be advertisements (Hsieh, Chen, & Ma, 2012). Benway (1998) theorized that users ignore banner ads because they are associated with unimportant information or “fluff.” If banner blindness can be attributed to advertisement disclosure, it may relate to how users misidentify sponsored and editorial content.

Examples of Disclosure

Effects of Advertising

Company

Utilizing native advertisements is a successful and profitable investment for brands (Boland, 2016). Sharethrough (2018), a native advertising agency, published a report with Interpublic Group indicating native advertisements were looked at 25 percent more often than traditional banner ads. Also, by placing ads natively, advertisers are gaining the perceived authority of the source (Conill, 2016).

In regards to brand attitude toward the sponsor, Sweetser et al. (2016) found that awareness of the content being advertising did not negatively impact the perceived trustworthiness of the sponsor. Although this attitude is dependent on the quality of the content within the advertisement.

Medium

The biggest impact native advertising holds for the mediums presenting it is gained ad revenue. Native advertisements are predicted to take up more than 74 percent of all advertising revenue by 2021 (Boland, 2016).

However, the use of native advertising may have a negative impact on the credibility of the medium particularly a print or news source (Cameron & Ju-Pak, 2000). The Society of Professional Journalists code of ethics (2019) states journalists should act independently and “deny favored treatment to advertisers.” The code of ethics goes on to highlight the importance of “distinguishing news from advertising and shun hybrids that blur the lines between the two.” As sponsored content by definition is the blurring of the lines between editorial content and advertisements, its ethicacy may be called into question.

Schauster et al. (2016) took a qualitative look at professionals in the fields of journalism, public relations, and advertising to gauge their professional opinions on native advertising. The researchers found that while their participants believed native advertising to be a necessity in the financial sustainability of the modern news model, professionals in the field found it overall unethical.

Conill (2016) further points out that by placing ads natively, advertisers are gaining the perceived authority of the source. However, it is surmised that there is a distinct difference between source credibility and message credibility. If this distinction between message and source credibility can be made by consumers, it could aid the discussion that disclosure is sufficient in differentiating advertisements from editorial content (Appleman & Sundar, 2016).

Effects of Advertising (continued)

Consumers

Supporters of native advertising claim that a reasonable person should be able to identify native advertising from authentic content (Schauster, Ferrucci, & Neill, 2016). However, studies have shown that a majority of people are unable to correctly identify it even with proper disclosure. (Wojdynski & Evans, 2015, Hyman et al., 2017).

A national study of college advertising students found that one-in-four could not correctly identify “sponsored content” as advertising. This study also found “one-fifth of students misidentified legitimate news articles as advertising” (Fullerton, McKinnon, & Kendrick, 2020, pg.14). For the general population these numbers are more concerning with one study reporting 92 percent of adults studied were not able to correctly identify paid content from non-paid content (Wojdynski and Evans, 2016).

This misidentification can be particularly troubling considering a Pew Research survey found that young adults (18-29 years) rated social media as their preferred platform for news consumption compared to TV, radio, and print (Shearer, 2018). By using social media platforms as their primary news source, the younger generations may be particularly vulnerable to native advertisements (Nee, 2019).

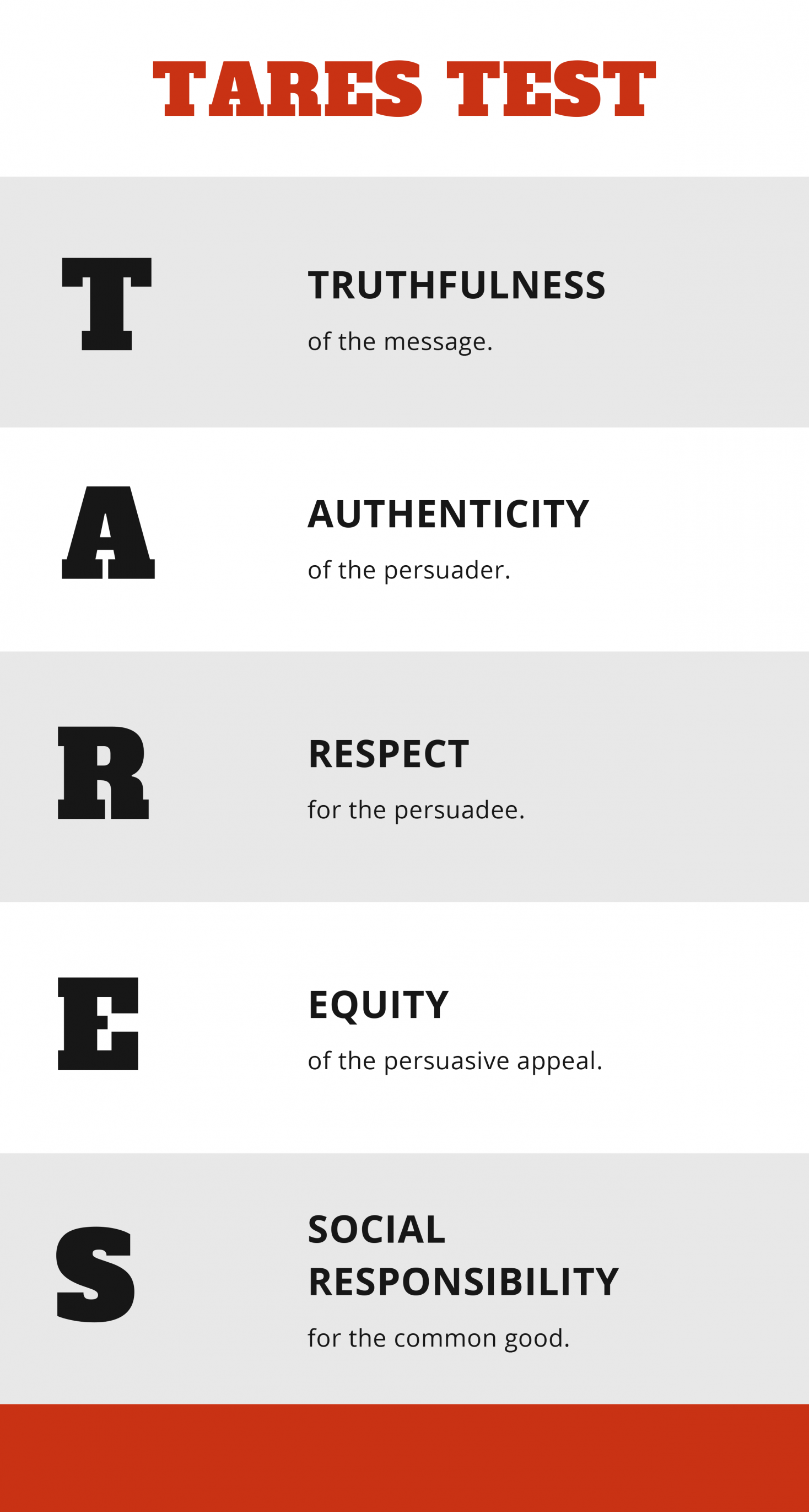

The TARES Test

An important part of ethical decision making is the ability to defend your choices. To aid in this process, we will examine the TARES test as a guide for making and defending ethical choices. The TARES test was developed by Baker and Martinson (2001) to focus on five principles for ethical persuasion. This framework functions under the theory of utilitarianism, which maintains that the results of an action are equally important to the action itself when evaluating its ethicality (Patterson, Wilkins, & Painter, 2019).

TARES is an acronym for truthfulness (of the message), authenticity (of the persuader), respect (for the persuadee), equity (of the persuasive appeal), and social responsibility (for the common good). These attributes are echoed throughout varies codes of ethics in the communication field including that of the Public Relations Society of America.

Truthfulness and Authenticiy

Truthfulness of the Message

Trust is essential in the field of public relations and presenting misleading information or misrepresenting information breaks that trust. In order to maintain trust, it is important that public relations professionals be truthful in their messages. Truth in this context does not mean only literal truth, but also conceptual, complete, unobstructed truth (Baker & Martinson, 2001).

To determine if a message is expressing the full complete truth, ask yourself the following questions about the message you are crafting:

| Has the message deemphasized important information? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Does the message represent the whole, complete truth? Was information left out in order to misdirect the persuadee? (Deaver, 1990) | Would I feel the message were complete if given to me in the provided context? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) |

| Does the message lead people to believe what I myself do not believe? (Bok, 1989) | Is the information withheld critical in allowing the persuadee to make an informed decision? (Fitzpatrick & Gauthier, 2000) | Does the message deceive people either explicitly or implicitly? (Bok, 1989) |

Authenticity of the Persuader

The TARES test focuses on the responsibility the communicator carries in developing messaging. As such the authenticity of the persuader must be called into question. When crafting messaging, you must evaluate your own motivations, loyalties, and attitudes regarding the message (Baker & Martinson, 2001). In order for the persuader to be authentic in their actions, they must believe in the product or idea they are communicating to the public

To explore your own authenticity on a matter ask yourself the following questions:

| Do I personally believe in this product? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Do I personally believe the persuadee will benefit? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | By putting out this message am I perpetuating corruption? (Martinson, 1999) |

| Is this cause or product something I would personally advocate for? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | In participating in this action is my integrity being called into question? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Am I happy to take responsibility for this message? (Waltz, 1999) |

Respect and Equity

Respect for the Persuadee

Respecting the persuadee means the persuader does not see the persuadee simply as a means to the end of selling their product or idea, but rather that the persuader considers the ramifications of any messaging on the persuadee and the public at large (Baker & Martinson, 2001). The well-being of the persuadee must be called into question and considered in any form of messaging so that the persuadee may make a well-informed, uncoerced choice. This concept goes back to the idea that the results of the action are equally important as the action itself.

Asking yourself the following questions will aid you in insuring you are treating the intended persuadees with respect as consumers and individuals:

| Does this message allow persuadee to act with free-will and consent? (Cunningham, 2000) | Does this message pander to or exploit its audience? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Have I taken the rights, and well-being of others into consideration with the creation of this message? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) |

| Will the audience benefit if they engage in the action the message portrays? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Does the information adequately inform the audience? (Cunningham, 2000) | Is the message unfair or to the detriment of the audience? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) |

Equity of the Persuasive Appeal

In the TARES test, the terms equity and fairness are used interchangeably. Equity refers to the balance of treating each persuadee with the same level of respect and concern. Persuasive appeals must not unjustly target a demographic without the ability to comprehend the message or exploit vulnerable populations. Exploitation refers both to the message itself and the motivations of the persuader. The TARES test specifically tasks communicators to examine their messaging, not only from their own perspective, but also to consider the intended audience to determine if the message is equitable (Baker & Martinson, 2001).

Asking yourself the following questions will help to determine if the message is equitable to all involved and to those targeted:

| Will the audience understand they are being persuaded not informed? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Have I unfairly targeted a specific or vulnerable population? (Patterson & Wilkins, 2014) | Would I feel this message was equitable if presented to me or someone I love? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) |

| Does this message exploit a power differential? (Gauthier, 2000) | Does the message take into account the special needs or interests of the target population? (Cooper & Kelleher, 2000) | How can I make this message more equitable? |

Social Responsibility and Ethical Decision Making

Baker (1999) explained that a communicator must consider their responsibility to the community over that of their raw self-interest. Self-interest in this context includes profits and career success. The common good in social responsibility signifies that, as persuaders are members of the community, the overall benefit to the community should be examined when creating persuasive messages (Baker & Martinson, 2001). Moyers (1999) argues that persuaders are a privileged voice in society and as such share a responsibility to improve and not hinder the communal well-begin. Persuaders should consider social responsibility on both the macro and micro levels. They must consider how each message will affect an individual and group and balance that information in order to create a message that positively impacts society (Baker & Martinson, 2001).

To measure the social responsibility of a message ask yourself the following questions:

| Does this message help or hinder public trust? (Bok, 1989) | Does this message allow for consideration of opposing views? (Moyers, 1999) | Does this message create the opportunity for public dialogues? (Cunningham, 2000) |

| Will having, or not having, this information lead to harm for individuals or groups? (Fitzpatrick & Gauthier, 2000) | Have the messages’ potential negative impacts been taken into account (Baker & Martinson, 2001) | Does this message unfairly depict groups, individuals, ideas or behaviors? (Baker & Martinson, 2001) |

Balancing the Elements of the TARES Test

It is important to note that at times the elements within the TARES test may conflict with one another. This conflict results in an ethical dilemma. Kidder (2009) defined an ethical dilemma as a ‘right-versus-right’ decision. With any ethical decision-making situation, there is not always a clear correct answer. For instance, when being truthful can negatively impact the public, an ethical dilemma occurs, calling for the need to question the social responsibility of the piece.

In ethical decision making there is not always a clear answer. The TARES test is designed to start a conversation in order to make the messenger consider the ethical implications of the message. Each element should be compared and weighed against the overall good versus the overall evil of the message and the potential ramifications of the message.

Case Study: Flat Tummy

One of most successful forms of native advertising is the use of social media influencers to promote products on social media sites. An influencer is defined as an individual with a large social media following who uses that clout to persuade people to purchase products or services (Kirwan, 2018).

Influencers are generally considered to have an expertise in a field in which their followers share an interest such as fashion or food (Hall, 2016). This perceived expertise gives the influencer a greater effect in persuading their followers.

Instagram, the photo sharing social media application created in 2010, has grown its user base to include a recorded 37 percent of Americans in 2019 with 67 percent of those users being between the ages of 18-29 years, according to a Pew Research survey (2019).

Advertisers have successfully moved into this space by utilizing influencers. Ninety-four percent of marketers found influencer ads to be successful, providing 11 times the rate of investment when compared to traditional advertisements (Ahmed, 2018). In 2016, 40 percent of Twitter users reported that they had purchased something based off an influencer’s tweet (Karp, 2016).

One aspect making influencer marketing so successful is that influencer ads are considered to be more authentic than traditionally branded ads (Talavera, 2015). Furthermore, Swant (2016) found that people rate influencer opinion equal to that of their friends.

Credibility is an important factor for influencers as it directly impacts their ability to persuade their followers (Hall, 2016). Lou and Yuan (2019) found that influencers' trustworthiness or credibility resulted in more positive thoughts toward the brands the influencers were promoting. To enhance credibility, many brands pay celebrity endorsers to advertise their product.

According to Wong (2018), the Kardashians are reported to collect six-figure payments for their sponsored Instagram posts.

Case Study: Flat Tummy (continued)

To demonstrate how an influencer can utilize the TARES test we will examine a controversial Instagram post made by Kim Kardashian West. In May of 2018, Kardashian West posted an ad for a hunger suppressant lollipop from the company Flat Tummy.

In this post, Kardashian West did include #ad. Although she was not criticized for product promotion, controversy arose over the product she endorsed. Backlash stemmed from followers accusing Kardashian West of perpetuating unhealthy dieting habits. Fellow influencer/actress Jameela Jamil responded to the post referring to Kardashian West as a “terrible and toxic influence on young girls” (Mahdawi, 2018). Kardashian West deleted the post.

This example showcases how FTC disclosure regulations are not enough to conclude whether an ad is ethical or not. It further illustrates how acting unethically can harm an influencer’s public image. To better understand the functionality of the TARES test we will walk through the process by considering the above ad. As with all ethical dilemmas, your reasoning may differ from others.

The advertisement is not truthful in its claim to provide users with a flatter tummy. A Harvard medical school professor told the Guardian that “dietary supplements sold for detox or weight loss are snake oil, plain and simple” (Wong, 2018).

Case Study (continued): Authenticity

Authenticity refers to the persuader's use and honest belief in the product. While the Instagram ad does depict Kardashian West with the lollipop in her mouth there is no indication that it is a product she uses on a regular basis.

An anonymous staffer from Flat Tummy who helped direct influencers on their Instagram photos alluded that they did not expect influencers to actually use the product they were promoting (Wong, 2018). It can be argued that by not being a genuine user of the product, Kardashian West is not showing due respect to her followers.

Regarding equity, there was an imbalance between knowledge presented in the ad when compared with knowledge the buyer would need to make an informed decision about purchasing the product.

Social responsibility can also be questioned in this ad. Critics of the ad pointed out that the timing of the ad being posted during Mental Health Awareness Week was especially troubling (Mahdawi, 2018). An estimated 20 million women and 10 million men in America have struggled with an eating disorder according to the National Eating Disorders Association (2019). Ads such as those for Flat Tummy lollipops perpetuate an unhealthy and irresponsible view of body expectations (Wong, 2018).

In this case, it also is important to consider the difference between law and ethics. The post followed FTC disclosure guidelines and was therefore legal. Instagram does have policies in place to lessen the inclusion of ads that may show a negative self-image (specifically warns against before/after photos and zoomed body parts) in order to sell health, fitness, or weight loss products. However, the policies apply only to paid Instagram advertisements.

The policies do not apply to the Kardashian West post and to other posts from paid endorsers (Wong, 2018). Today, the Instagram “flattummyco” has 1.7 million followers. In its rise to success, it has focused the majority of its marketing efforts on social media (Wong, 2018). Although Kardashian West, suffered backlash from the initial Flat Tummy lollipop post, she and her sisters have since endorsed other Flat Tummy products, including Flat Tummy shakes and Flat Tummy tea. With the subsequent posts, online backlash also has followed (Nzengung, 2019; Zollner, 2020). It is the questioned unethical actions, not legal infringement, that has caused backlash for the Kardashians as Flat Tummy endorsements. Although the sponsored posts are legal, the application of the TARES test may indicate they are not necessarily ethical.

Discussion Questions

- If Kardashian West put her decision to post about the Flat Tummy lollipop through the TARES test, would she have realized the ethical questionability of the company?

- Would she have decided to promote the product?

- Would she have experienced the backlash and harm to her public image?

- What would you have advised Kardashian West to do in this case?