Lesson 2: Fake News Content

President Donald Trump popularized the term “fake news,” using it to describe negative news coverage during the campaign and after his 2016 election. After Trump’s inauguration ceremony, media disputed whether the audience size was accurately reflected in his description of the enormous crowd. Responding to the inauguration coverage, Press Secretary Kellyanne Conway coined the term “alternative facts” (Fandos, 2017).

Since Trump took office, his accusations of “fake news” coverage have increased and his description of what is “fake” has expanded. According to Keith (2018), Trump’s tweets about news that he deems “fake,” “phoney,” or “fake news” has increased both in scope and frequency. These tweets reference “fake books,” “fake dossier,” “Fake CNN,” and “fudged news reports.” An NPR Analysis of Trump’s tweets found that he included the words “fake news” in 389 posts (Keith, 2018). Not only has media content been called into question, but trusted news organizations have been labeled as “fake news” providers.

Next Page: Fake News ContentFake News Content

A convergence of factors in today’s digital society has resulted in a range of challenges involving the origin, dissemination, veracity, and effects of many types of messaging. Contributing to these challenges are the relative ease of self-publishing online, the re-dissemination of messages by both individuals and organizations, the speed at which information is circulated, and the blurring of lines between advertising and editorial content (Conill, 2016).

These factors often compound the difficulty of determining the source, the intent, and the accuracy of information consumed. While the ultimate goal of news coverage may differ for journalists and public relational practitioners, both professions operate under the same ethical principle of telling the truth. However, truth, itself, is now at odds with a cultural shift where people often associate news with the word “fake.”

With truth called into question, the definitions of fake news vary. Legal analysts confine the definition to “online publication of intentionally or knowingly false statements of fact” (Klein & Wueller, 2017, p. 2), while other scholars include political “spin,” propaganda, and native advertising (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018).

Fullerton, McKinnon and Kendrick (2020) conclude that “fake news” includes content that may be misleading, sensationalized or deliberately false.

Indeed, “fake news” is a very broad term. To develop a typology, Tandoc, Lim, and Ling (2018), reviewed 34 academic articles focusing on “fake news” that includes six categories: news satire, news parody, fabrication, manipulation, advertising, and propaganda.

Often the contributing factor to understanding fake news is the content’s motivation. While it may seem obvious to distinguish credible news from “fake news” stories, it is not. Results from a 2016 Buzzfeed survey found that “fake news headlines fool American adults about 75% of the time” (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018, p. 137). Fake news stories may be more obvious to the audience, such as humorous stories trending on social media.

However, fake news also may be advertising that is strategically crafted to look like editorial content while promoting a more meaningful agenda (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018). Despite the lack of agreement upon “fake news” definitions and categorization, the phenomenon has critical implications for the functioning of a democratic society, press freedom, professional communicators and individual citizens.

Types of Fake News

Lesson 1 provided an in-depth look at one of the most pervasive types of fake news: native advertising. With native advertising, the persuasive message content is generated by the client. Thus, native advertising and other sponsored content allows strategic communicators the opportunity to shape the media content.

Lesson 2 focuses on the remaining types of fake news: satire, news parody, fabrication, manipulation and propaganda (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018). With these types of fake news, the organization does not create the editorial content. Instead, it is often the target of the messages created by a third-party source.

Therefore, public relations professionals must understand the types of “fake news” that could potentially threaten their clients or stakeholders.

From a public relations perspective, it is important to consider fake news types focusing on both facticity and level of deception.

By examining fake news stories, as well as strategic responses, PR professionals can understand how to successfully and ethically respond to fake news stories.

While the ultimate goal of news coverage may differ for journalists and public relational practitioners, both professions operate under the same ethical principle of telling the truth.

However, truth, itself, is now at odds with a cultural shift where people often associate news with the word “fake.” Despite the lack of an agreement upon definition and the various types of fake news, the phenomenon has critical implications for the functioning of a democratic society, press freedom, individual citizens and professional communicators.

Satire and Parody

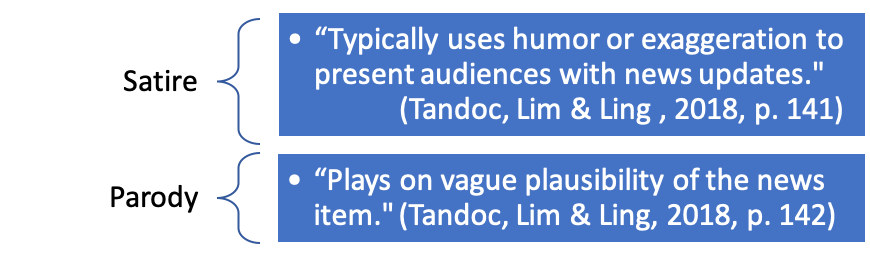

Content that typically makes fun of news programs and uses humor to engage with their audience members can be classified as news satire (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018). Often, the overall intent of spreading this type of information is to provide entertainment by suggesting humorous critiques of political or pop cultural events.

For example, Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” is an example of a highly appraised fictitious news program that uses satire to poke fun at current events. While still categorized as “fake news,” satirical information does not come from journalists, but rather comedians or entertainers (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018).

While similar to satire, parody is another type of fake news. The difference between the two is simply a function of how the humor is used. “Instead of providing direct commentary on current affairs through humor, parody plays on the ludicrousness of issues and highlights them by making up entirely fictitious news stories,” according to the scholars, Tandoc, Lim and Ling (2018). Specifically, political parody outlets capitalize on the “vague plausibility of the news item” (p. 142). The Babylon Bee is a leading parody site where they claim the motto, “totally inerrant in all its truth claims.”

Satire and Parody (continued)

It is important to note that studies include satire and parody under the category of fake news because of their formatting. Unlike other types of misinformation, satire and parody have no intention to cause harm which significantly separates the two from other types of fake news. Because of this, there is some controversy surrounding the spread of this type of information. On one hand, scholars like Tandoc, Lim and Ling (2018) claim humorous articles and trendy social media headlines can help people become aware of cultural events.

Yet, at the same time, research also proves that satire and parody sites can have a strong influence on a person’s belief system and may be more persuasive than people might think (Tandoc, Lim and Ling, 2018). When criticized for encouraging “fake” satirical sites, like The Babylon Bee, by mainstreamed journalists, The Babylon Bee’s Editor in Chief, Kyle Mann, responds to his critics, ironically, through satire (Andros, 2020).

Fabricated Content/Imposter Content

While satire and parody play on humorous attacks, this first level of “fake news” does not require immediate attention due to its widely acknowledged entertainment value. However, this next level of fake news, fabrication, requires a different response due to its lack of facticity and intent to deceive.

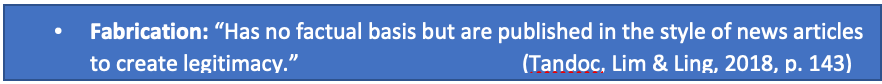

This type of information has no factual basis; however, the stories are presented or “published in the style of news articles to create legitimacy,” and often are believed to be a trustworthy source because partisan organizations often present information with some neutrality (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018, p. 143).

According to the scholars, Tandoc, Lim and Ling (2018) research acknowledges that this type of information is often spread for the purpose of financial gain or now, more frequently, by artificial intelligence online sources.

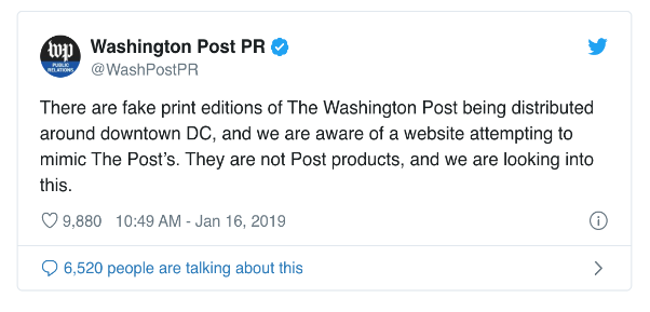

On May 1, 2019, newspapers, appearing identical to The Washington Post, were distributed on the streets in Washington D.C. The headline, “Unpresidented,” appeared in large bold letters alongside a story which claims President Trump resigned from office. According to one of The Washington Post reports, the purpose of the newspaper was to show “the future and how we got there — like a road map for activists,” said Jacques Servin, a leader of the initiative (Heil & Farhi, 2019). The article also points out that the collection of fabricated materials cost nearly $40,000 to print and distribute which signifies the level of planned intention and commitment of spreading disinformation (Heil & Farhi, 2019).

In response to the distribution of look-alike newspapers, The Washington Post took immediate action by issuing a disclaimer warning that the paper was not legitimate on their Twitter account, “Washington Post PR.”

This was an important effort by public relations professionals because they shined light on the spread of disinformation as quickly as possible before releasing an official response. Later on, a spokeswoman Kris Coratti, responded by writing, “We will not tolerate others misrepresenting themselves as The Washington Post, and we are deeply concerned about the confusion it causes among readers. We are seeking to halt further improper use of our trademarks” (Heil & Farhi, 2019). While communication professionals may not have the ability to stop fake news stories from happening, implementing an instant response, by utilizing social media, can quickly stop false information, as fast as it is being shared.

Fabricated Content/Imposter Content (continued)

It is important to realize that it is not just the public who can be misled by entirely false information. Unfortunately, sometimes credible news outlets are fooled and often they may not realize it until it is too late.

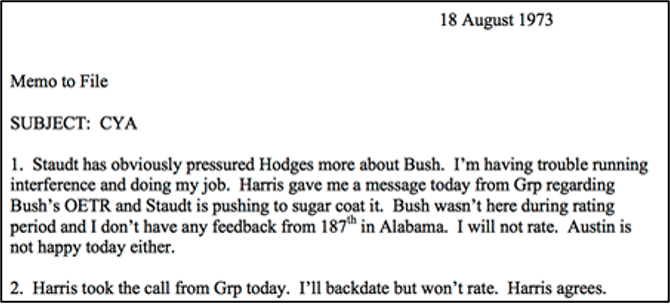

One instance, referred to as Rathergate, demonstrates just how strong fabricated messages can be. In 2004, Dan Rather, a journalist for CBS, presented six documents during an episode of the broadcast TV show, “60 Minutes.” The files being discussed, known as the Killian documents, contained information about President Bush’s service in the Texas Air National Guard (Rutenberg and Zernike, 2004). The news was believed until only two months before the presidential election happened. Breaking news reported that CBS failed to factcheck the documents before broadcasting it to the public.

It was later learned that the Killian documents were not written on a typewriter in 1973, but instead created on Microsoft Word (Rutenberg and Zernike, 2004). The experts suggest it would have been impossible to develop such a document that many years before.

In response to the allegations, Andrew Heyward, the CBS President said, “We should not have used them. That was a mistake, which we deeply regret," according to an article written by The New York Times by Rutenberg and Zernike.

Additionally, Rather, the CBS reporter, also gave a personal statement regarding the fake news story that got him fired. He writes, "I want to say personally and directly I'm sorry" (Rutenberg & Zernike, 2004). This is just an example of how powerfully persuasive messaging can be. Often, timing is a key factor to the spread of political fake news stories. One might only image how the courses of history would have changed if the files were not declared as yet another believable “fake news” story.

Manipulated Content-False Connection

While fabrication is 100 percent false, the next type of fake news actually has some truth to it. Manipulation can be described as news stories that use “real images or videos to create a false narrative” according to the scholars Tandoc, Lim & Ling (2018, p. 144). Despite there being some truth, using an adaption of imagery to sensationalize a story still misleads consumers by developing a false connection.

One example of manipulated content was an incident that widely become known as “kids in cages.” Photos taken by The Associated Press in 2014 were published with an article discussing Trump’s immigration story claiming that the administration had “lost track of nearly 1,500 immigrant children” according to the AP. The story trended on social media and grabbed the attention of many due to its particularly compelling images of kids confined behind what looks like a fence. One tweet, by Antonio Villaraigosa, the LA mayor, wrote “Speechless. This is not who we are as a nation” (Flaherty & Woodward, 2018).

The compelling photo was in fact real and Trump’s immigration policies were reported accurately; however, the photo placed next to the news story manipulated the content to indicate differently. In response to these allegations, President Donald Trump himself tweeted, “Democrats mistakenly tweet 2014 pictures from Obama’s term showing children from the border in steel cages. They thought it was recent pictures in order to make us look bad, but backfires” (Flaherty & Woodward, 2018).

While there may be some truth to manipulated content, the falsehoods overshadow otherwise important facts or information. Given that Trump popularized the term “fake news” in the wake of the presidential election, incidents that question the credibility of otherwise trusted sources continue to contribute to the lack of believability from consumers. If something is only somewhat true, then it is still fake news.

Propaganda

Finally, the last type of fake news is propaganda. Scholars define this kind of disinformation as “news stories which are created by a political entity to influence public perceptions” (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018, p. 146). It’s important to highlight the fact that propaganda often may have some plausible truth to it; however, the information is paired with strong political bias intended to persuade those who read and, or, see the presented information. (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018).

While propaganda is not commonly seen throughout the United States due to our freedoms and democratic run government, it is still a type of fake news that communicators should be able to recognize.

For example, the world has been upended by the global pandemic caused by the COVID-19 virus in 2020. Yet, the concern surrounding the virus turned from being just a medical issue to a political one.

The New York Times reported that the Chinese government had created several thousands of fake Twitter accounts in order to spread disinformation online about the coronavirus and where it initially began. Many of the social media stories claimed that the virus originated in the United States. The propaganda filled messages gained lots of traction online and resulted in a large number of retweets and likes.

In response to the widespread disinformation, Twitter took down roughly 150,000 fake accounts purposely trying to “amplify China’s leading envoys and state-run news outlets” claimed The New York Time’s article (Conger, 2020).

As time went on, government entities, news organizations, and the public became more aware of how the virus actually came to spread. As a result, the false Twitter accounts shifted their messaging in March of 2020 and began comparing the response initiatives between the United States and China. Specifically, China was referred to as the “responsible big country” in comparison to the United States who was called on to “put aside political bias,” according to The New York Times (Conger, 2020).

In response to the fake Twitter accounts, a statement was issued from the director of the International Cyber Policy Center, Fergus Hanson, who directly worked alongside the social media company to put an end to the propaganda. “Persistent, covert and deceptive influence operations like this one demonstrate the extent to which the party-state will target external threats to its political power,” Hanson said (Conger, 2020).

Case Study – Fake News Dissemination: Pizzagate

Dissemination

A convergence of factors in today’s digital society has resulted in a range of challenges involving the origin, dissemination, veracity and effects of many types of messaging including news, “fake” news, sponsored blog posts and native advertising, to name a few.

Contributing to these challenges are the relative ease of individual self-publishing online, the re-dissemination of messages by both individuals and organizations, the speed at which information is circulated and the blurring of age-old lines between advertising and editorial staffs – historically, “church and state” (Conill, 2016). These factors can compound the difficulty of determining the source, intent, and accuracy of much of what is consumed on the Internet and in social media.

If “fake news” is false, or only partly true, how does it spread? As simple as it sounds, sometimes people don’t realize what is real or what is fake. In fact, a Pew Research Center survey found that 23 percent of Americans say they have shared fake news whether that be knowingly or not (Mitchell, Holcomb, & Barthel, 2016).

Yet the spread of fake news stories, despite anyone’s underlying intentions, are contributing to a growing dissemination of falsehoods. Therefore, it is no wonder that 64 percent of U.S. adults blame fake news stories for confusion surrounding basic facts about politics or events in the country (Mitchell, Holcomb, & Barthel, 2016).

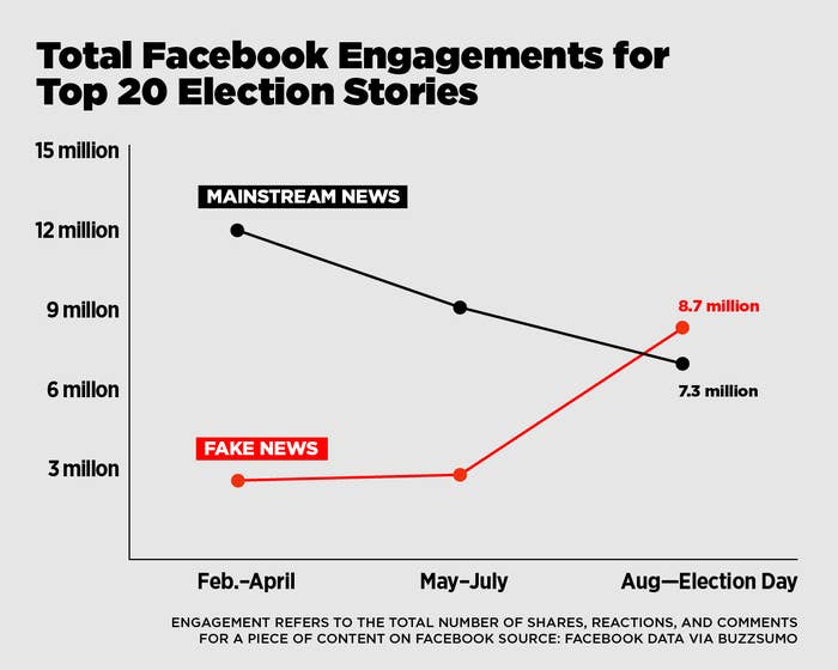

Social media networking sites have completely changed how fake news is spread. The leading networking site, Facebook, with well over 1 billion users, now is said to contribute to providing news to 44 percent of the population (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018). While the platform is enjoyed for its instantaneous connections and free flowing information, unfortunately, many users have participated in the spread of fake news stories.

In fact, a BuzzFeed News analysis found that Facebook trended more top news stories, before the 2016 presidential election, even over its major news counterparts including The New York Times, Washington Post, Huffington Post, NBC News, and others (Silverman, 2016). Unfortunately, one of those high-profile stories was Pizzagate.

Case Study – Fake News Dissemination: Pizzagate (continued)

Pizzagate Case Background

Just before the Presidential Election in 2016, a man walked into a pizza parlor and fired gunshots. While no one was injured, this incident happened because of false information being shared online.

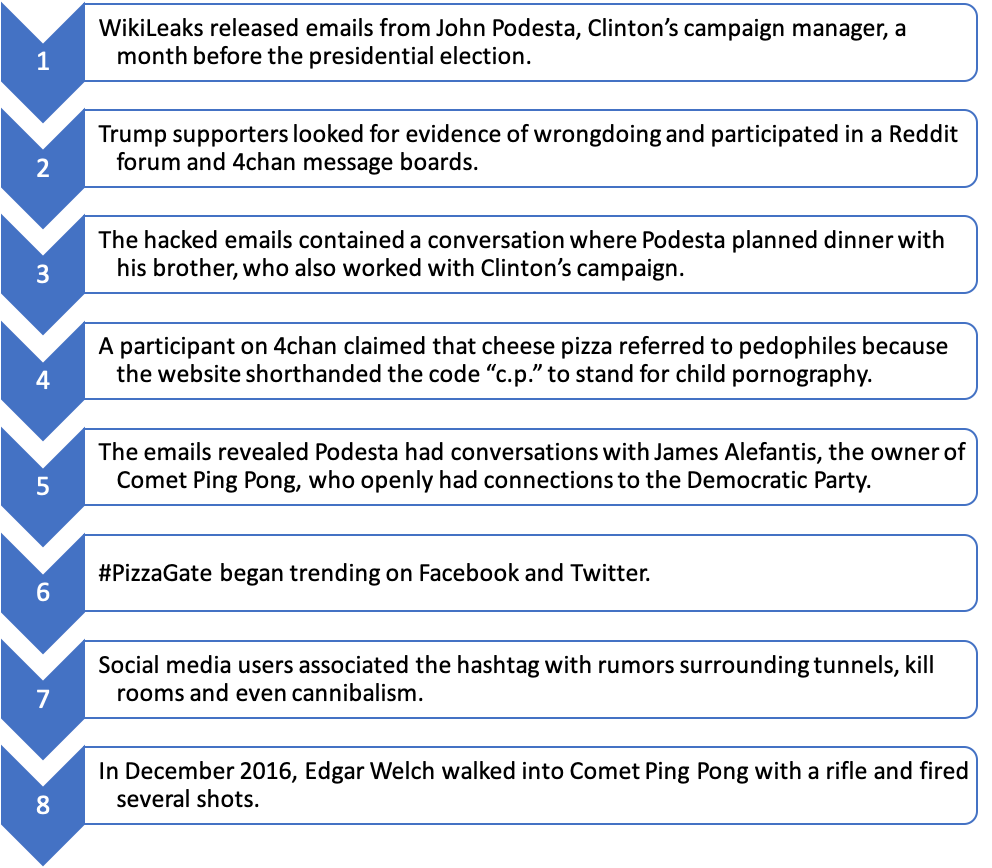

A conspiracy theory circulated on social networking sites which claimed the Comet Ping Pong restaurant, located in Washington D.C., was hiding a child prostitution ring run by Hillary Clinton and her campaign manager. This case study will examine fake news dissemination through an article published by The New York Times, written by Aisch, Huang and Kang (2016). The authors developed a step-by-step timeline briefly explaining how the fake news spreads.

Consequences

In many cases, when people ignore fake news, it spreads. However, this case study proves that fake news can still result in tangible actions. (Tandoc, Lim & Ling, 2018). Thus, fake news can have consequences. The spread of this particular disinformation threatened much more than just a brands reputation, it put lives at risk.

James Alefantis, Comet Ping Pong’s owner, blamed the unfortunate event on the individuals who took part in spreading false information. He said in a statement to The New York Times, “I hope that those involved in fanning these flames will take a moment to contemplate what happened here today and stop promoting these falsehoods right away” (Aisch, Huang & Kang, 2016).

Discussion Questions

- Who should be blamed for the spread of fake news?

- After reflecting about the extreme consequences from the spread of fake news exhibited by the Pizzagate scandal, do you think that the accusations of disinformation went too far?

- At what point, if any, should the spread of false information be stopped?

- How would you recommend that Comet Ping Pong respond to guard their reputation?

- What should the Democratic Party have done to respond to the false allegations?

Discussion

The spread of satire, parody, manipulation, fabrication, and propaganda is likely inevitable in modern society. Indeed, social media plays a large part in its imminent spread.

News is no longer simply reported by journalists or distributed by public relation professionals. The audience is also an active participant in creating and sharing news. Unfortunately, fake news stories gain power as misinformation and disinformation are spread. Practitioners need to be aware of the potential for fake news coverage and should consider ways to manage and combat fake news.

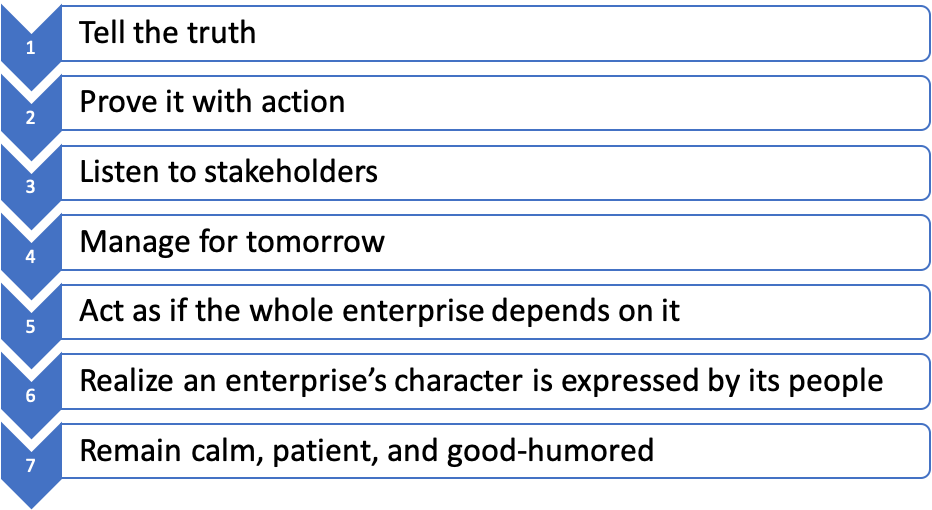

During a fake news crisis, practitioners should keep in mind the Page Principles to guide their ethical reasoning and strategic recommendations.

Discussion (continued)

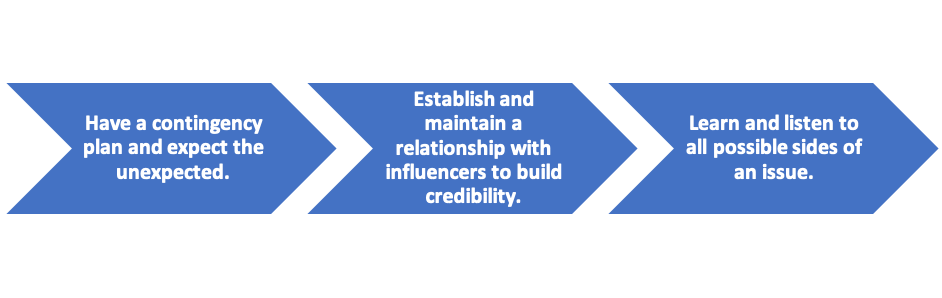

It is also important to consider recommendations from public relations professionals who have maneuvered the fake news environment. Through interviews with 21 public relations professionals in agencies and corporations, Ewing and Lambert (2019) developed strategic recommendations for combating online fake news attacks.

First, practitioners should have a contingency plan. If ever the subject of fake news coverage, it is better to have developed a strategic response strategy in advance. Research also revealed that during a fake news crisis, practitioners should engage with online influencers. Although this may seem counterintuitive, online influencer hold significant power. Thus, engaging influencers may aid practitioners in shaping the online conversation.

Ewing and Lambert (2019) offer the following ideas for online engagement:

- Build goodwill in advance

- Inspire advocacy

- Correct false information

- Be responsive and transparent

- Integrate media relations and social media strategies

Their findings also suggest that listening to stakeholders is a key factor in preparing for a fake news crises. Taking a proactive approach, practitioners should listen for potential issues, to identify influencers, and to include diverse perspectives.

Discussion Questions

Discussion Questions

- Compare and contrast the different types fake news.

- Reflect on your own experiences and encounters with fake news stories. Think of an instance for each level of fake news and analyze their individual public relations approach.

- Of all the Page Principles, which do you think is the most important ethical value for public relation professionals to uphold and why?

- With future technological developments, do you anticipate that fake news will become more or less of a problem?

- How can a client avoid being the focus of fake news?

- How can public relations professionals manage fake news crises?